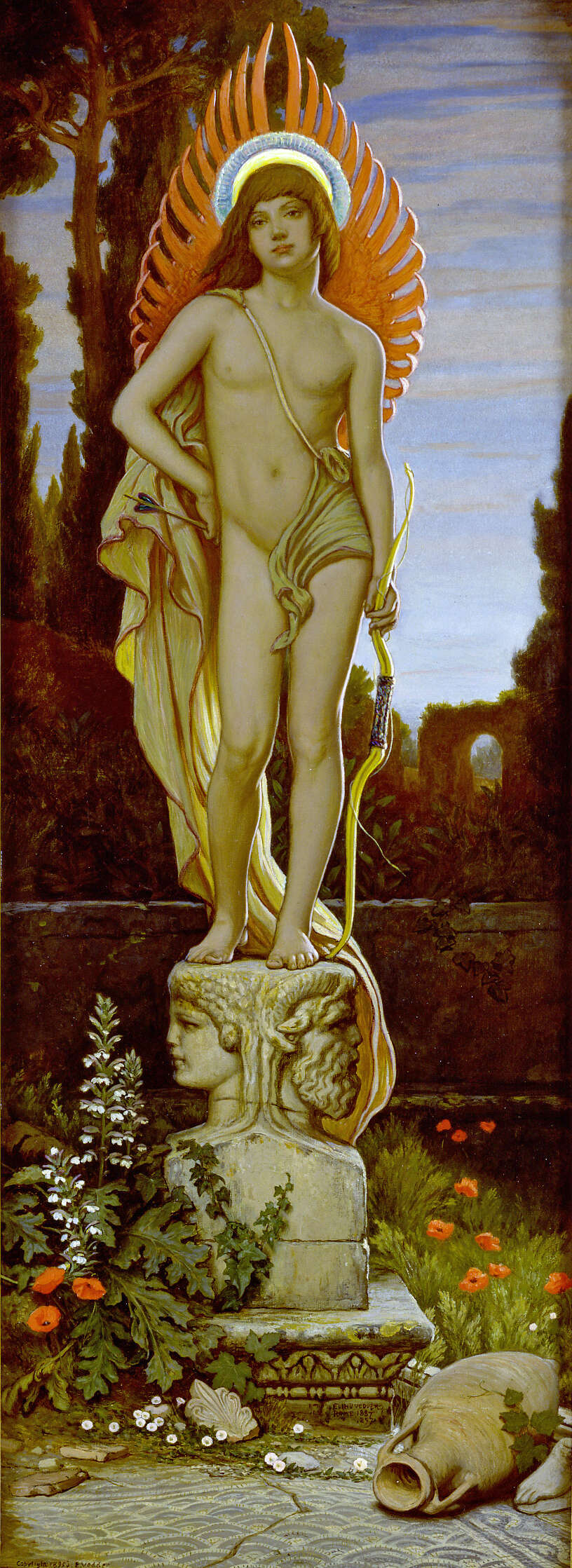

Elihu Vedder (American, 1836-1923), Superest Invictus Amor (Love Ever Present), 1887, Oil on canvas, 34 ¾ x 12 ¼ inches

As I write this in mid-June, it has been just about thirteen months since my last entry in this blog. While saying my wistful goodbyes, I also shared with you an arresting lithograph by the American painter, illustrator, and printmaker Rockwell Kent. Those of you who visited the exhibition American Modernisms at the Rollins Museum of Art would have seen it on the walls, part of my exploration of the figurative tradition in American modernism. I am excited to report that Dr. Heller has invited me back this summer, to perform research on a new group of objects coming into the collection. The group, a partial and promised gift of the Martin Andersen-Gracia Andersen Foundation, will add both depth and breadth to the RMA’s already stellar collection of American art. I will be sharing some of my insights into this new corpus of objects in this space as I work through them, starting with a group of works that will also be on display in the museum this fall. Consider this a kind of head start on your appreciation of our new friends (it is a common affliction of art historians to consider works of art their personal friends, probably part of our tendency to see animation and life in what might otherwise be considered inert matter).

In that post a year ago I wrote about Rockwell Kent, an artist with a long and prolific career who is best remembered today for his illustrations of a canonical work of nineteenth-century literature, in this case Moby-Dick. For my first post of this new set of blogs, I would like to share Superest Invictus Amore, by the American painter Elihu Vedder. Vedder, like Kent, is best remembered today for his own illustrations to accompany a major work of literature, in this case Edward FitzGibbon’s 1859 translation/adaptation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Vedder is one of those interesting figures in the history of American art. Like Kent, his career was long and prolific, and nearly every major collection of American art contains a Vedder or two. Yet, despite this ubiquity, he has often seemed marginal to the broader story of American art, dismissed as an eccentric oddball whose work bore little relevance to the broader currents of Americanist art history. In her book Painting the Dark Side: Art and the Gothic Imagination in Nineteenth Century America, the art historian Sarah Burns notes that he was one of a number of artists pushed to the margins due to his failure to conform to the landscape tradition. That book was published in 2004, and even as she wrote it some of the artists she considered, such as Thomas Eakins and Albert Pinkham Ryder, were achieving greater recognition amongst scholars and the public. There is a sense, however, in which Vedder has lagged stubbornly behind, his strange and visionary paintings difficult to access even for professionals.

In recent years, however, that has begun to change. Scholars of American art have begun to consider Vedder in the context of his time and place. For her part, Burns considers a group of strange, enigmatic early paintings Vedder produced during his time in New York during the Civil War (except for this brief interlude, Vedder spent his career in and around Rome) in the context of his membership in the café society centered around Pfaff’s Restaurant in New York. In a ”Paired Perspectives” section in the journal American Art in 2015, the art historians Sylvia Yount and Akela Reason offered a pair of historiographic interventions into Vedder’s Rubaiyat drawings. For Yount, the series shows Vedder’s integration into the trans-Atlantic culture of Aestheticism, while for Reason they show his ongoing interest in themes of spiritual uncertainty, part of a larger cultural conversation prompted by the destruction of the Civil War and the destabilizing influence of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species.

What does this efflorescence of Vedder scholarship mean for Love Ever Present? To be honest, I’m not entirely sure. The painting appears sporadically in the extant Vedder literature. In a 1979 exhibition catalogue from the National Museum of American Art (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum), it appears in the context of Vedder’s immediate post-Rubaiyat production, during which the artist—newly financially stable thanks to the success of the book illustrations—continued to explore his interest in the interplay between the earthly and the spiritual. In her review of the exhibition, the art historian Barbara Groseclose mentions the painting as an example of Vedder’s tendency to get too cute with his classical references, even going so far as to call the painting insipid.

I’m not sure I agree, but it is an odd painting, depicting Cupid perched on a Janus-headed pedestal with personifications of Psyche and Pan, respectively the object of Cupid’s romantic love and the personification of physical love. This iconographic analysis is interesting enough, as far as it goes. I’m excited, however, for the painting to receive greater attention now that it’s part of the RMA collection. What might we make of its odd format (tall and thin)? Its ornate frame? What of the broken crockery, the Classical ruins, and the plant matter? Cupid’s stylized wings, too, draw my eye. The time is ripe, I think, for someone to further unravel this painting’s mysteries.

Grant Hamming, Ph.D.

American Art Research Fellow

To read more on this work by Elihu Vedder, visit our Collection page.