A pioneer of conceptual photography, Lorna Simpson is best known for her large-scale works combining images and text. Simpson’s photography often questions and challenges conventional views on gender, sexuality, race, identity, and culture in the United States. Many of her pieces created between 1985 and 1995 incorporate text to complicate the meaning of the image and provide commentary on a variety of issues.

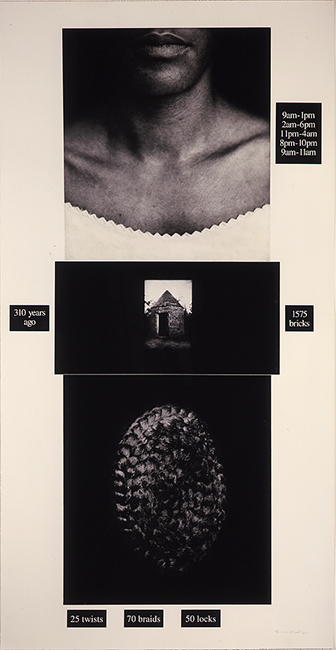

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) Counting, 1991 Photogravure and screenprint 73 3/4 x 38 in. Museum purchase from the Anniversary Acquisition Fund. 1998.10.

Education and Early Career

Simpson discovered photography while she was a student at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. An internship at the renowned Studio Museum in Harlem led her to meet a number of contemporary artists, most notably Carrie Mae Weems. Weems urged Simpson to join her in graduate school at the University of California, San Diego.

The curriculum at UCSD was heavily tilted towards performance, conceptual, and other intellectual forms of artistic production. Simpson quickly evolved a practice that combined her interest in photography with careful—and usually quite pointed—interrogations of the systems and structures that undergird American society, particularly its racism and misogyny. During her early period, dating roughly from 1985 to 1995, Simpson made a series of works that blended photography—most often pictures of anonymous Black women—with snippets of text that both explain and complicate the images they accompany.

Counting

Counting, like many works from Simpson’s early career, engages directly with the historical—and historicized—experience of Black femininity. Three photographs—of a woman, a smokehouse, and woman’s hair—are surrounded, buttressed, and complicated by a series of numbers.

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Counting, 1991

Photogravure and screenprint

73 3/4 x 38 in.

Museum purchase from the Anniversary Acquisition Fund. 1998.10.

Simpson’s work often challenges portrait conventions by foregrounding Black women while obscuring or effacing their faces. This complex process both counteracts and highlights their historical erasure through racial and sexual violence. The inclusion of the smokehouse, which is connected to the era of slavery with the label “310 years ago,” makes this relationship explicit. The work’s assertive, even obsessive, insistence on counting calls further attention to the history of slavery. It by recalls the fact that, for much of American history, people of African descent were little more than commodities, property to be counted on one side or the other of a ledger.

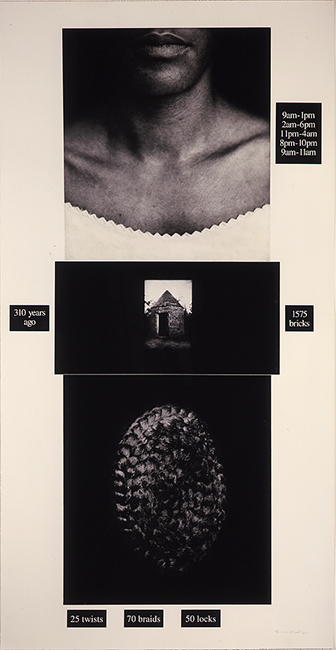

Untitled (from SITE Santa Fe Benefit)

Untitled (from SITE Santa Fe Benefit), which Simpson executed to benefit a contemporary art space in Santa Fe, New Mexico, continues her engagement with historical memory, archives, and racialized violence.

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Untitled (from SITE Santa Fe Benefit), 1995

Four-color electrostatic heat transfer on felt

9 x 11 in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund. 2020.2 © Lorna Simpson. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

The print reproduces two pieces of found ephemera, both likely from the nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. On the left, a pair of young white women hold one another as they tip over a riverbank, about to plunge into the water below. On the right, a pair of blindfolded Black men in military uniforms are in the process of being executed by firing squad. A mixture of white and Black spectators, the latter most likely enslaved laborers and the former their enslavers, look on.

The two pairs of figures—black and white, male and female—are united by their shared postures, as well as by the pair of black bars which slightly overlap both scenes. By pairing these two formally similar but thematically quite different images, Simpson calls attention to the very different historical subjectivities that undergird white and Black Americans. A pose indicative of a whimsical sunny day is rendered, for people of African descent, into a sinister symbol of systematic racialized violence.

Later Experiments in Different Media

Around 1994-1995, Simpson began to step away from the pseudo-portraits of Black women that had defined her early career, in part because of a sense of exhaustion she felt from her investigations of historical memory and violence. She did not entirely shed her interest in Black femininity, however, embarking on a series of works depicting—and sometimes using real examples of—wigs. This continued her interest in the cultural importance of Black women’s hair, which also appears in Counting and other works of her early career.

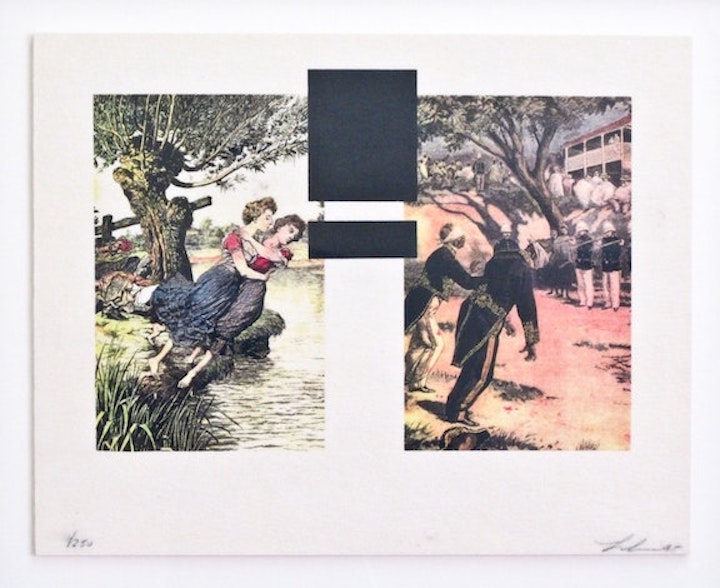

Upper and Lower Case Wigs

Upper and Lower Case Wigs subverts her usual formula somewhat, by representing a male moustache and beard as “wigs.” The work represents a more playful moment in Simpson’s oeuvre, one that nevertheless helps her to interrogate trouble gendered distinctions in American society, in this case the difference between male and female norms regarding hair.

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Upper and Lower Case Wigs, 1994

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Peter Norton. 2020.64 © Lorna Simpson. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In Upper and Lower Case Wigs, Simpson comments on race and gender by exploring representations of hair, an often-important part of African American history, identity, and culture. Using humorous text and a hierarchical placement of the “upper case wig and lower case wig,” Simpson questions notions of propriety and examines how perceptions of gender and culture shape our relationships and experiences.

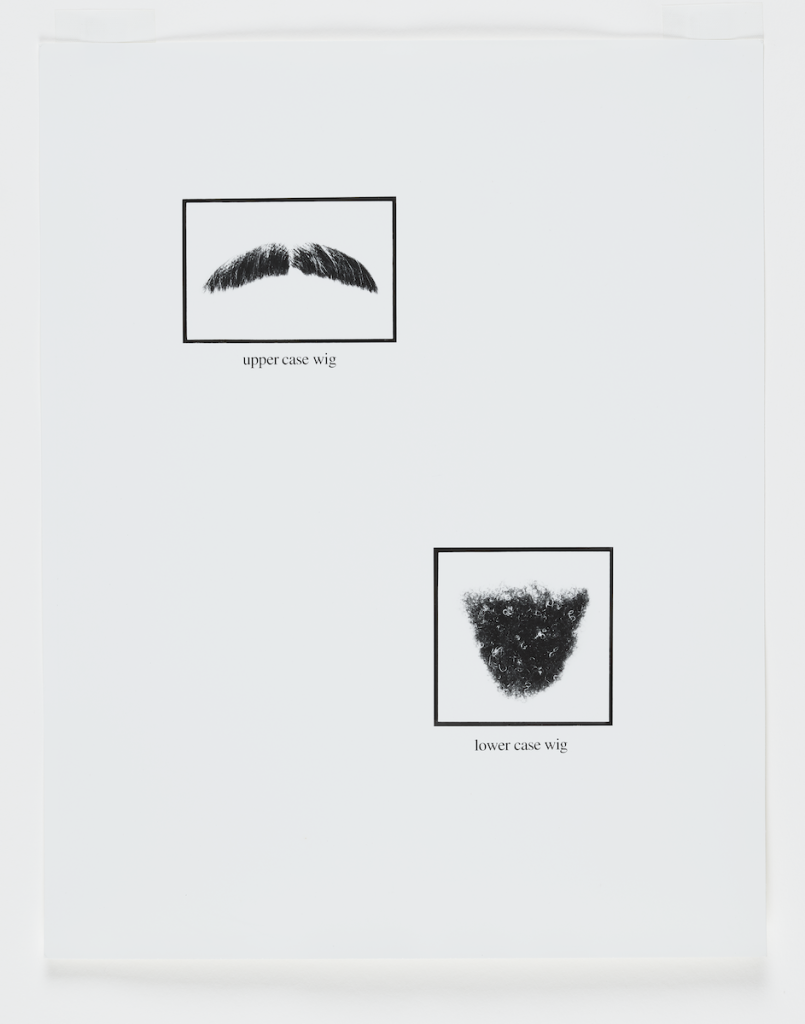

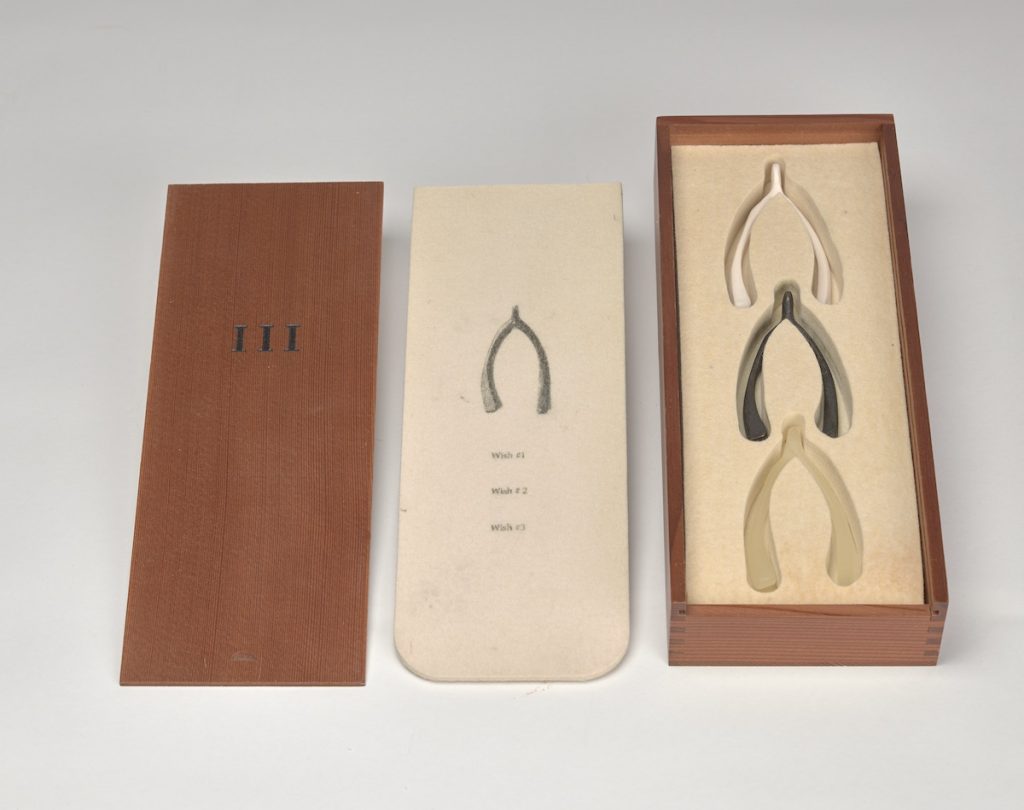

III

Simpson also experimented with sculpture and installation works during the 1990s. The recurring wishbone motif in works of this period alludes to the fragility and resistance of the body. It reflects on the act of, and expectations around, wish-making.

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

III, 1994

Cedar box containing felt, ceramic, bronze and silicone rubber

13 1/2 x 5 5/16 x 2 1/8 in.

Gift of Suzanne Delehanty in honor of Teagan Walsh, Rollins Class of 2020 2020.38

This work, III, was one of 5,000 commissioned by the Peter Norton Family Foundation to be mailed to friends and family as a holiday greeting. The wooden box with the engraved roman numerals III holds three wishbones made of ceramic, bronze, and rubber. The tradition of pulling the wishbone at holiday dinners comes into question when some of these materials would likely be unbreakable, asking the viewer to consider whether or not all wishes can be easily granted.

View Lorna Simpson’s works at Rollins Museum of Art

You can view III in the What’s New? Recent Acquisitions exhibition at the Rollins Museum of Art Tuesday – Sunday through May 12, 2024.

Look for Simpson’s works in future Rollins Museum of Art exhibitions. Bring a friend, admission is FREE.