“I have measured out my life with coffee spoons.” –T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

“…if there is one sector of society which should be cultivating deep thought, it is academic teachers.” –Maggie Berg & Barbara K. Seeber, The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy

As I make my daily writing progress during this Academic Writing Month (#AcWriMo, and the Rollins version #RoAcWriMo), I sat down this morning to finish a chapter I’m writing with Peter Felten about a “slow liberal arts.” The chapter–specifically about teaching and learning–will be available in 2019, but I want to take a moment to share some of what’s been on my mind about the broader campus implications for faculty work.

This is my first time participating in AcWriMo, and it has been a revelation for me. I’m not a write-every-day kind of writer, even during my designated periods of writing. I also appreciate Helen Sword’s work challenging the universal applicability of this technique (see “‘Write Every Day!’: A Mantra Dismantled” and Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write). But committing to take the time to get some writing done each day–no matter how little, no matter what that writing looks like–has changed how I experience the rest of my day. I have felt more present in meetings, consultations, and conversations with others. I’m sleeping better. I’m making the transitions between my home day and my work day more smoothly. In short, I’m doing some of the most important invisible work that makes me better at my visible work.

It’s not simply a matter of productivity. Much of the time I set aside for AcWriMo isn’t actually spent writing. It’s bigger than that, less quantifiable and less visible. It’s the chance to shift into uninterrupted thinking, immersion, “‘engrossment,'” “timelessness,” “‘thinkology,'” “‘flow,'” and “deliberation over acceleration”–all ways of expressing what Berg and Seeber describe as “what we [should be] modeling for each other and for our students” (p. 21, 26, 28). “We need time to think, and so do our students,” they assert. “Time for reflection and open-ended inquiry is not a luxury but is crucial to what we do” (p. x).

With this in mind, I offer the following possibilities as a challenge to campus cultures that make this necessary work elusive, guilt-inducing, or the stuff of dreams:

- Let’s all take a good look at our list of meetings, “the ultimate time-suck,” especially meeting for meetings’ sake. Are we holding meetings that really could be emails, hallway conversations, or folded into other meetings? I’m not advocating for less conversation. I’m just suggesting that productive conversations don’t always need to be systematized into regular time slots that may be more frequent and longer than they actually warrant.

- Before I got tenure, I had to find a way to get my required writing done without getting up at 3am every day. My students dropped in to see me throughout day, and not always for issues related to our classes. Aside from the emotional labor of ‘being there’ for students who just needed someone to talk to, this time one-on-one with students added up to more hours than I could possible manage, and more emotional support than I knew how to offer. When would I prep for class? When would I work on committee homework? When would I write? I finally realized that kind of availability was unsustainable, so I committed to closing my door when needed and hanging a sign that said something like this:

- I’m writing. Faculty members are required to publish their writing to keep their jobs, and good writing takes some uninterrupted time. [Or perhaps … I’m preparing for class. To be fully present in the classroom, I need to reread the materials, think carefully about how the day’s plan follows what’s happened in our previous classes, and develop thoughtful activities to support your learning.] If you really need to see me right now, knock. Otherwise, please come see me during my office hours, or call or email me.

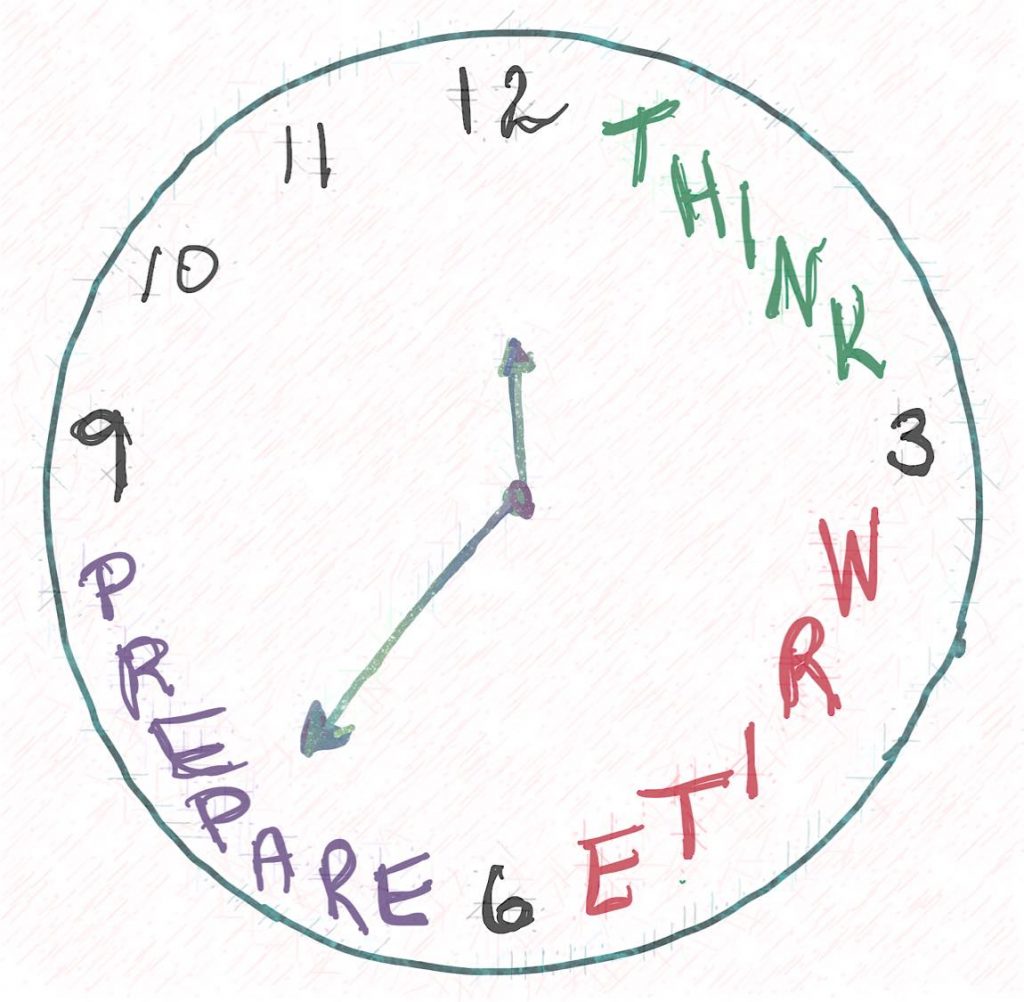

- Finally, if November is Academic Writing Month (#AcWriMo), designed to help academics set aside time to write, develop a sense of community in this challenge, and raise awareness of the need for this time, when is Academic Thinking Month (#AcThiMo)? We don’t want to interrupt the time “off” promised by winter and spring breaks in January and March, and semesters end in either April and May, so let’s do February. February 2019: the inaugural #AcThiMo. Sign up here: bit.ly/AcThiMo2019

Who’s with me? Think about it.

In response to a few requests, here are two signup sheets, and I’ll email you closer to February 1 with instructions and suggestions.

- public signup sheet: bit.ly/AcThiMo2019

- private signup sheet: bit.ly/AcThiMo