I, like many people across the country, have been using YouTube yoga videos to break up my routine and introduce a little more physical activity in my life during these long months of stay-at-home orders. Even as my state of Virginia continues to open up, I doubt I will be going to a gym any time soon, so rolling out my mat in front of the television remains a daily joy. And while I often look forward to practicing just as soon as I finish my work researching the CFAM collection, I never expected the two to overlap. That is, until I started looking at the museum’s extraordinary group of works by modern American painter, sculptor, and printmaker Arthur B. Davies.

Arthur Bowen Davies has traditionally occupied a place in the history of American art that is at once central and marginal. On the one hand, he was instrumental in the planning of the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art (popularly called the Armory Show because it was held in the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City), a huge exhibition which introduced cutting-edge European painting to many Americans for the first time. Davies’s colleagues marveled at his seemingly instinctual understanding of European modernism, and his almost autocratic leadership coupled with bold selections for the show helped to ensure its success. Despite this understanding, however, scholars have long seen Davies’s own art as less adventurous than the artists he championed, engaging in a dreamy Romanticism more reminiscent of the 1890s than the 1920s, though his work was quite popular with his contemporaries.1 At the same time, Davies himself was remarkably secretive about his daily life, going so far as to require a secret knock before he would admit anyone to his studio. Friends chalked this secrecy up to a maniacal focus on work, but a few intimates knew the truth: Davies was essentially a bigamist, living with one woman in Manhattan during the week and commuting Upstate to visit his official wife on the weekends. The secret did not get out until after his death, and even then his wife did her best to cover up the truth.2 The combination of these circumstances for many years served to limit discussion of Davies to his scandalous biography and his promotion of American art.3 Recently, however, scholars have begun to delve deeper into Davies’s rich oeuvre, exploring the ways in which his art engages with the intellectual and cultural currents of the early twentieth century.

One of those scholars is Robin Veder, whose work examines Davies’s work in the context of what she calls “body cultures,” which “…are historically specific physical practices and ideas that shape how bodies should look, feel, work, and move.”4 Davies—whose best-known works involve singular or multiple nude figures arrayed in a landscape—stood at the intersection of a complex series of discourses about the body. These included his interest in ancient Greek art, which he believed demonstrated the physical process of inhalation in a way that led to spiritual awakening; the exercises he performed to lessen the pain from angina; modern dancers such as Isadora Duncan; the motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge; the body posture exercises of François Delsarte and his American disciples; and theosophy, a new religious movement that blended elements of occult spirituality, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Neoplatonism.5 It was through the latter two that Davies became interested in yoga, in particular Surya Namaskar, known in English as the Sun Salutation.6 Those who practice yoga will recognize this series of postures, which is central to yoga as it is practiced today. For those who are less familiar, the key thing to know is that Surya Namaskar involves postures in which the chest is expanded to the height of the breath, extending upwards towards the sky.7

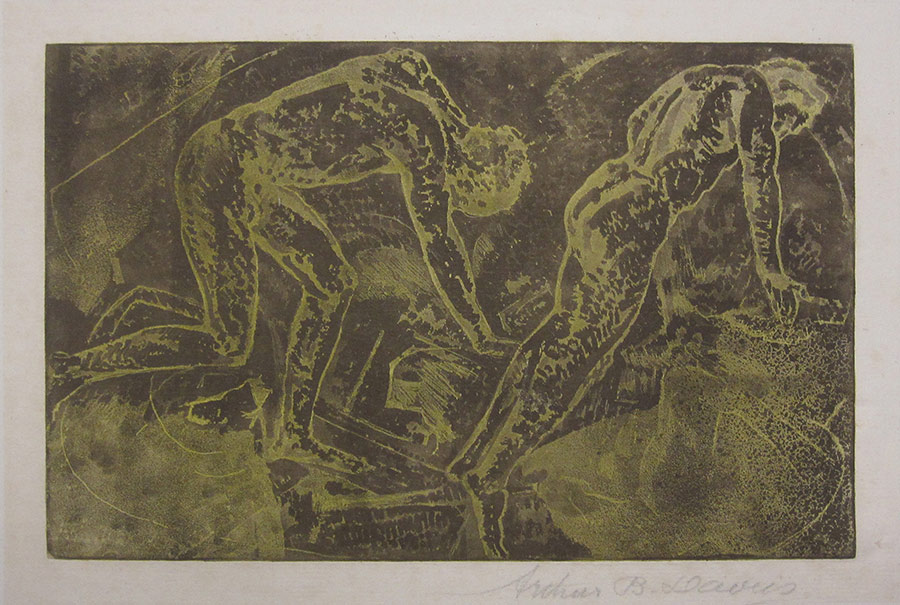

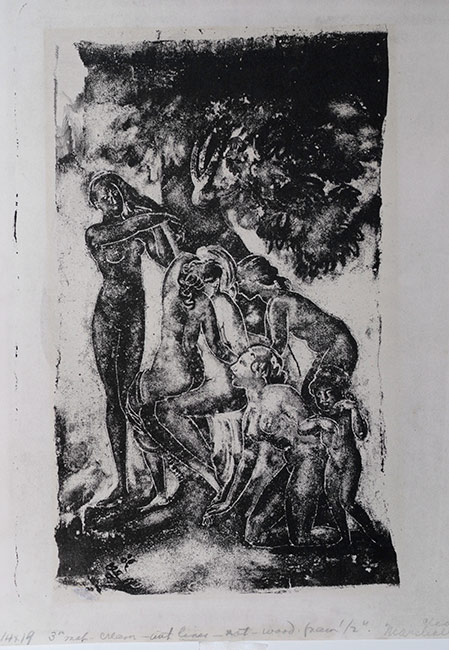

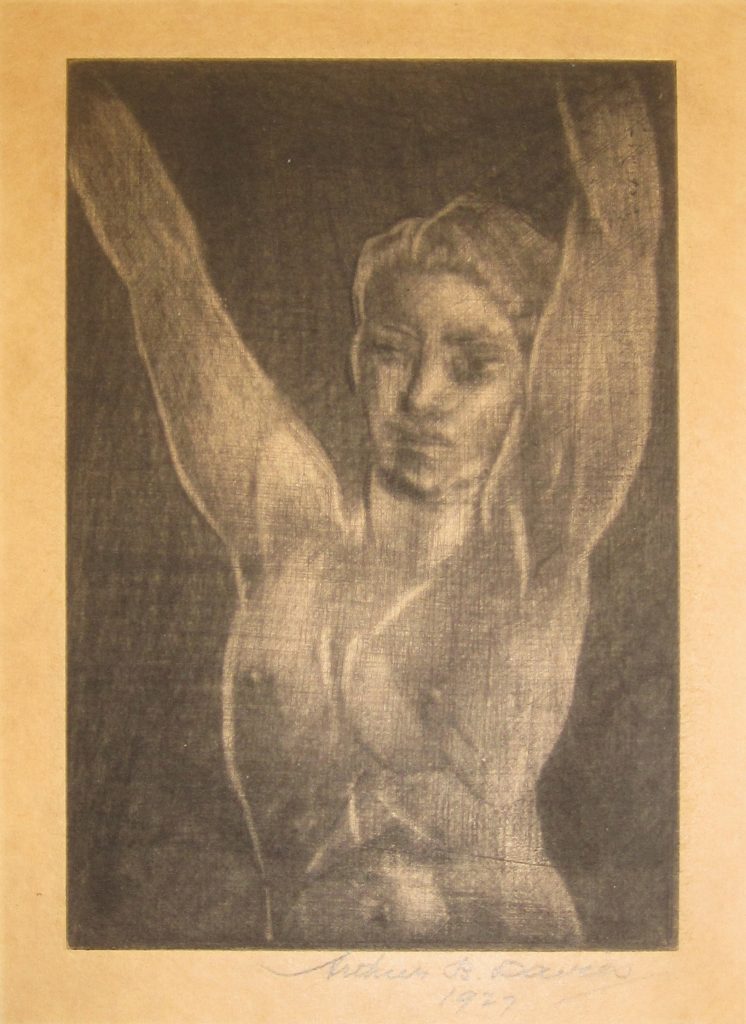

Once I was clued into this aspect of Davies’s practice, I

quickly realized that it was everywhere in his art. In Uprising, two

male figures—or, more likely, the same male figure represented twice—pushes

himself up from the ground and towards this extended-stretch posture. Figures

of Earth, too, seems to show a series of figures—or a single figure in

series—going through a variety of yogic or yoga-like postures as part of a

dynamic movement towards the sky, or, befitting the title, down towards the

ground. It is in Entreat most of all, however, where the influence of

yoga seems most pronounced. The mezzotint, with its hazy, almost wash-like use

of fine crosshatched lines, is ample evidence of Davies’ careful study of the

human form. The figure, with her taut muscles, extended arms, and chest full of

breath, is every bit the picture of potential energy. At the same time, her

focused eyes and serene face speak to a spiritual calm, a calm that Davies

believed came hand in hand with this posture. The next time I find myself

saluting the sun, I will undoubtedly reflect on Arthur Davies and smile.

1 Kimberly Orcutt, “The Problem of Arthur B. Davies,” in The Eight and American Modernisms, ed. Elizabeth Kennedy et al. ([New Britain, Conn.] : [Milwaukee] : Chicago: New Britain Museum of American Art ; Milwaukee Art Museum ; Terra Foundation for American Art : Distributed by the University of Chicago Press, 2009), 26–28.

2 Orcutt, 23–24. For an extensive and illuminating account of Davies’s life and its relationship to his work, see Bennard B. Perlman and Arthur Bowen Davies, The Lives, Loves, and Art of Arthur B. Davies (Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press, 1999).

3 Emily Willard Gephart, “A Dreamer and a Painter : Visualizing the Unconscious in the Work of Arthur B. Davies, 1890-1920” (MIT, 2014), 24.

4 Robin Veder, “Arthur B. Davies’ Inhalation Theory of Art,” American Art 23, no. 1 (2009): 61.

5 Veder, 59–69. See also Robin Veder, The Living Line: Modern Art and the Economy of Energy (Hanover, UNITED STATES: Dartmouth College Press, 2015). And Va.) Maier Museum of Art (Lynchburg et al., Modern Movement: Arthur Bowen Davies Figurative Works on Paper from the Randolph College and Mac Cosgrove-Davies Collections and Arthur B. Davies : Paintings from the Randolph College Collection (Lynchburg, Va.: Maier Museum of Art, 2013).

6 Veder, “Arthur B. Davies’ Inhalation Theory of Art,” 72–73.

7 Practitioners of yoga might recognize this posture as Anuvittasana or Hasta Uttanasana. I will avoid naming specific yoga poses—in Sanskrit and in English—from here on out, in order to make this legible for as many readers as possible.