Back in October, I wrote about the moment around the turn of the twentieth century when photography became art. In that post, I examined the work of F. Holland Day and Gertrude Käsebier, two of the most influential figures in the movement known as Pictorialism. Today, I would like to return to Pictorialism, this time to examine Alfred Stieglitz and his two protégés, Edward Steichen and Paul Strand. Together, these three men have come to be known as the “Big Three” of early American art photography, figures whose legacies tower above the field.1

Purchased with funds from the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.26

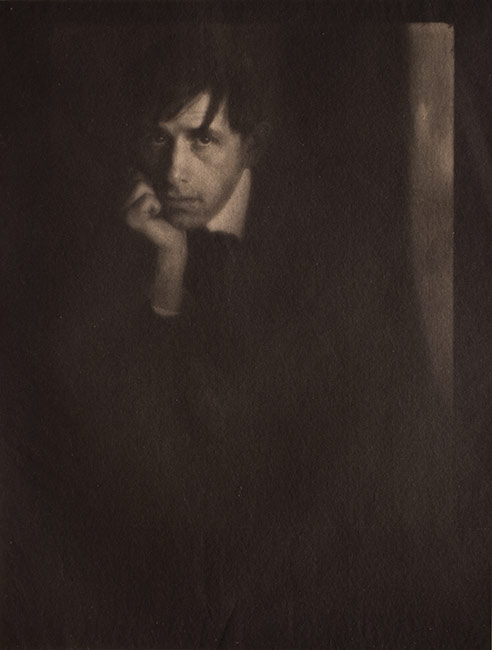

Stieglitz is one of the most famous figures in the history of American art, due both to his tireless promotion of a variety of painters and photographers as well as to his own innovations in the formulation of Pictorialism. In 1902 Stieglitz, after having consolidated New York’s two societies of amateur (meaning in this case artistic, as opposed to commercial) photographers into the wealthy and powerful Camera Club of New York, put on an exhibition of practitioners representing what he termed the Photo-Secession. Steichen, Day, and Käsebier were all included in this group, a fact which elicited bemusement from all three. For his part, Steichen later remarked that “In fact, no one but Stieglitz seemed to know what ‘Photo-Secession meant.” Stieglitz had taken the name from the Austrian Secession and similar avant-garde groups in Europe and intended it as a relatively loose affiliation of all the photographers then working in the Pictorialist style.2 Steichen’s Portrait of Clarence White (another member of the Photo-Secession) is a perfect example, using a variety of techniques to achieve a hazy, painterly style meant to evoke the style of French Symbolism as well as Tonalism, its American equivalent.3

Perhaps Stieglitz’s most important contribution to the Photo-Secession—and to photography more broadly—was Camera Work, the lavishly designed and printed journal he edited and published under the auspices of the Camera Club of New York. Stieglitz (assisted by Steichen) pioneered the use of the photogravure technique in its pages. Photogravure represents a hybrid between photography and printmaking, involving a photographic image transferred to a photosensitive metal plate and then fixed through the medium of etching. It allows for a relatively inexpensive reproduction that nevertheless retains a high level of fidelity to the original negative, and Stieglitz was obsessive about printing only from original negatives, always on a high-quality, translucent Japanese tissue. Such is the quality of these photogravures that they have become nearly as sought after as original photographic prints, a fact that to which the presence of Camera Work photogravures by Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand, Day, and Käsebier in the CFAM collection attests.4

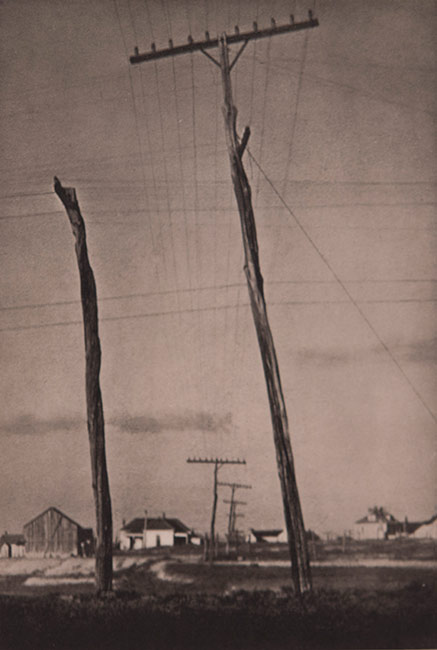

Telephone Poles, 1915,

Photogravure print

Purchased with the Michel Roux

Acquisitions Fund,

2013.27

During the fourteen-year run of Camera Work (from 1904 to 1917), Steichen was the photographer most heavily featured in its pages.5 The journal was eventually undone by the economic changes wrought by the American entry into World War I. For its last issue, however, Steichen was nowhere to be seen. Instead, Stieglitz chose to feature the work of his newest protégé. Paul Strand, who was ten years Steichen’s junior, had come to Stieglitz for advice at the outset of his career (just as Steichen himself had at age 22). Stieglitz, whose own approach to photography had been changed by the famed 1913 Armory Show that introduced European modernism, especially Cubism, to the American public, advised Strand to abandon pictorialism in favor of the unretouched realism known as Straight Photography.6 Telephone Poles is a prime example, relying not on painterly flourishes for its artistic effect but rather Strand’s careful selection of the scene for maximum visual impact. Steichen’s—and Pictorialism’s—era had passed, but his disappointment would be relatively short-lived. An avowed Francophile, Steichen threw himself into the American war effort, heading up the U.S. Army’s aerial photography division. After the war, he would become renowned for the fashion and portrait photographs he took as the senior photographer for Vanity Fair, eventually capping his storied career by becoming the first curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art.7 Today, he is often remembered as the most famous photographer in history, eclipsing both his mentor Stieglitz and his erstwhile rival Strand.

1 Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) and Malcolm R. Daniel, eds., Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand: Masterworks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York : [New Haven, Conn.]: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press, 2010), 11.

2 Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) and Daniel, 12.

3 Ronald J. Gedrim, “Peinture à La Lumière: 1898-1907,” in Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography, ed. Todd Brandow (Minneapolis : Lausanne : New York : In association with W.W. Norton: Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography ; Musée de l’Elysée, 2008), 84–85.

4 Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) and Daniel, Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand, 13.

5 Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) and Daniel, 13. The first issue was entirely devoted to Käsebier, a fact that rankled Steichen at the time.

6 Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) and Daniel, 18–21.

7 John Raeburn, A Staggering Revolution: A Cultural History of Thirties Photography, 2006, 62–63.