When I saw the listing on the CFAM website for the artist George Grosz, I wondered if someone had made a typo. Grosz, I knew, was a German-born artist best remembered for his scathing depictions of the corruption of interwar German society, a critical stance which earned him a spot on the early Nazi blacklists and resulted in his being stripped of his German citizenship in 1933.1 Shouldn’t I wondered, his name be spelled in the German fashion, as in Georg, without the final letter e? No, as it turns out, because Grosz Americanized his name. Interestingly, he did this not in 1938, when he became an American citizen, but rather in 1916, after the first of two stints of service in the World War I German Army (he was medically discharged both times). The move from Georg Groß to George Grosz served two purposes. The first was to distance himself from Germany, with which he was increasingly disillusioned. The second was to embrace the United States.2 Though he wouldn’t travel here until 1932, the young Grosz was infatuated with the country. This infatuation set him apart from his contemporaries in the Dada movement, most of whom viewed the United States suspiciously as a land of racial violence and capitalist oppression.3 Grosz’s enthusiasm for the country lasted, and he was one of the few German intellectuals fleeing Nazi persecution who willingly, even enthusiastically, crossed the Atlantic. 4

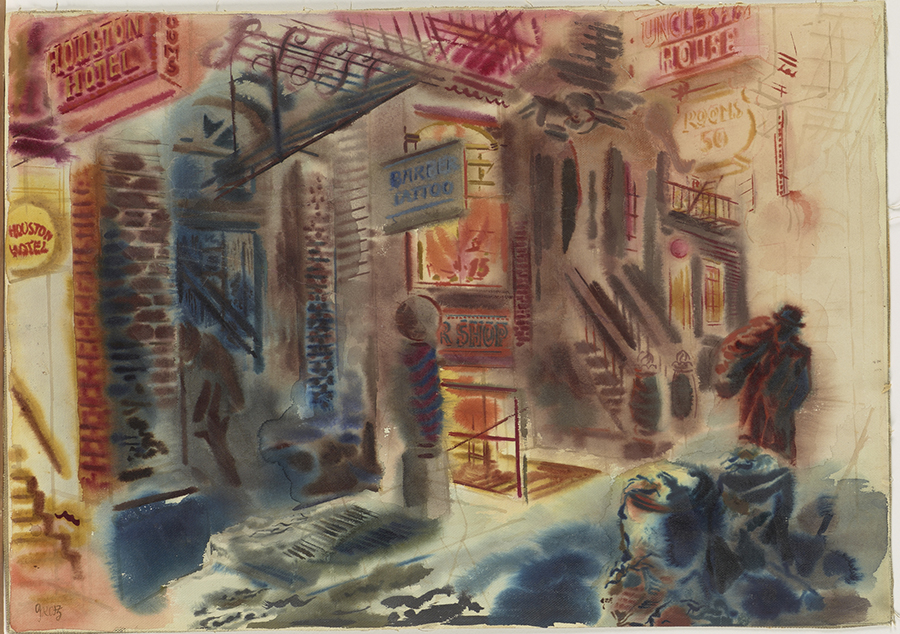

This knowledge—as it so often does—prompted another question. Why, if Grosz was so happy to leave Germany and come to the United States, does City Lights, the World War II-era watercolor in the CFAM collection, seem so, well, unsettled? Depicting Houston Street, which demarcates the southern border of Greenwich Village in Lower Manhattan, the work is a fine example of Grosz’s embrace of watercolor during his New York years.5 In it, he takes full advantage of the smeary, spontaneous quality of watercolor to depict the hallucinatory impact of bright nighttime lights. The scene represents an unassuming stretch of street, featuring a barber shop and a cheap hotel. Those who have spent time in New York will recognize the garbage overflowing its cans in the lower right, seemingly as much a feature of the wartime city as it is today. The bright, even acid colors create, to my mind, a claustrophobic atmosphere. This sense of dis-ease is even more striking in light of the pair of shadowy sinister figures who seem to converge on the viewer, one moving in from the right and the other half concealed by a doorway to the left. The Manhattan of City Lights is not a happy, welcoming place, but rather a scary one, full of both physical and psychic horrors.

What prompted Grosz’s shift to depictions of New York as a place of alienation? The art historian Barbara McCloskey, a foremost expert on Grosz, argues that it was Grosz’s increasing celebrity that did it. As reports of Nazi atrocities mounted, Grosz’s earlier Dada-era work was increasingly in demand. This caused dealers, journalists, curators, and the public at large to turn away from his American work—as well as his serious and sincere efforts to turn himself into an American artist—back to his German past. The artist felt that these earlier works, which Americans saw as deeply and stirringly relevant to the present moment, had been failures, unable to stop the Nazi rise to power. They were also persistent reminders of the country he had grown to loathe. The result was increasing isolation for Grosz, who turned more and more to introspective works of art that expressed his own feelings of futility. These feelings were exacerbated by ongoing money troubles as well as an overreliance on alcohol, causing further isolation.6 Grosz’s money troubles got to the point that he was forced to resume teaching at the Art Students League in 1949, a vocation which his letters and diaries reveal he detested.7 As Germany emerged from the war, divided but rebuilding, he found himself torn between his adopted country and his homeland, neither of which felt fully welcoming. His wife, Eva, pressed him to return to Berlin, and he finally agreed to do so in 1959. The couple sold their houses on Long Island and Cape Cod, moving back to the German capital and renewing their old lives there, amidst the rubble. Sadly, however, Grosz died of heart failure a few weeks after their return.8 He left an artistic legacy that captured and defined life in two of the world’s great cities during some of their most tumultuous years.

1 Ralph Jentsch et al., George Grosz: Berlin-New York, 1st ed (Milano : London: Skira ; Thames & Hudson [distributor], 2008), 193.

2 Jentsch et al., 73.

3 Jentsch et al., 71–76.

4 Barbara McCloskey, The Exile of George Grosz: Modernism, America, and the One World Order (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015), 3–4.

5 Jentsch et al., George Grosz, 221.

6 McCloskey, The Exile of George Grosz, 3–6.

7 Jentsch et al., George Grosz, 232.

8 Jentsch et al., 238.