One of the paintings in our current exhibition, Dangerous Women: Selections from the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art , depicts an episode from the story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, as recounted in the biblical book of Genesis. Young Joseph, while in Potiphar’s service, catches the eye of the master’s wife, who tries to seduce him on a day when they are alone in the house. Joseph refuses her advances and flees, leaving his coat behind. Rebuffed, Mrs. Potiphar tells her husband that the “Hebrew slave” tried to rape her, and uses the coat as incriminating evidence, which lands Joseph, once Potiphar’s trusted advisor and overseer of the household, in prison (Gen.39.5-20).

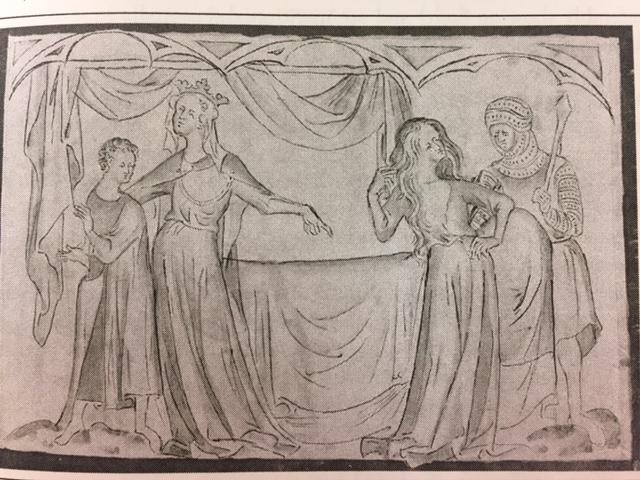

The story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife is not exclusively a biblical tale. Versions exist in ancient Egyptian literature, post-biblical rabbinical exegesis, Christian writings, and medieval fables. Not surprisingly, the story often changes to reflect contemporary realities and to make its message more poignant. For instance, during the Middle Ages, several romances circulate where the female protagonist is the queen of Egypt instead of Potiphar’s wife. An illustration of such texts is seen in the Queen Mary’s Psalter, a 14th century manuscript now in the British Library.

The queen is seen twice in the image on folio 16: on the left with Joseph, and on the right telling an armed guard about the attempted rape. While in the Bible she goes directly to her husband, in the medieval tale the king is out hunting, so she tells a palace soldier. Notably, her appearance is quite different when comparing both sides of the illustration. On the right, her hair is loose, the clothes in disarray, the crown and head cloth gone. This representation takes on the standard appearance of a rape victim at the time, whose visual attributes were recognizable and repeatedly mentioned in medieval law treatises.

The question becomes: is this visual identification of Mrs. Potiphar with a rape victim simply an enhanced representation of her cunning, or are we encouraged to look more kindly upon her? Since the literature of medieval Europe does not directly spell it out, we cannot be sure. What we do know is that depictions of the story multiply starting in the late 15th century, especially in painting, and that torn clothes, visible flesh, and rumpled bed sheets become standard in such depictions, including the painting in our exhibition. However, the way Potiphar’s wife is portrayed changes. Starting in the 15th century, the theme of the concubine, the mistress who lures a man into adultery, becomes popular in literature and parallels a new concern about sexual morality in European society. Women are increasingly depicted as seductresses, even where the storyline does not necessarily warrant that characterization. Even paragons of virtue such as Judith and Lucretia are now pictured semi-nude, as if to imply the latent enticement women cannot help but provoke. One of the most popular texts around the turn of the 16th century was The Power of Women, a compilation of tales that illustrated the great sexual power that women have over men and depicted men as hapless victims.

The painting in our exhibition illustrates this point well. Made in the workshop of the 17th-century Italian painter Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Guercino, it is a copy of the master’s original (today in the collection of the National Gallery in Washington, DC). A very young Joseph struggles to get away from the half-naked Mrs. Potiphar, who looks like a beautiful ancient goddess; she does not quite touch him, and yet he is gesturing almost frantically to escape her grip. It seems rather hard to believe that this clearly frightened boy has any chance to resist her embrace and flee – which, of course, makes the moral message all the more poignant. In this context, it is little wonder that the story becomes a favorite for artists and patrons alike: it offered the perfect narrative vehicle for a tale of seduction and resistance, virtue and vice – not to mention the opportunity to depict a beautiful half-naked woman – while also telling the story of a (male) hero resisting temptation.

The painting in our exhibition illustrates this point well. Made in the workshop of the 17th-century Italian painter Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Guercino, it is a copy of the master’s original (today in the collection of the National Gallery in Washington, DC). A very young Joseph struggles to get away from the half-naked Mrs. Potiphar, who looks like a beautiful ancient goddess; she does not quite touch him, and yet he is gesturing almost frantically to escape her grip. It seems rather hard to believe that this clearly frightened boy has any chance to resist her embrace and flee – which, of course, makes the moral message all the more poignant. In this context, it is little wonder that the story becomes a favorite for artists and patrons alike: it offered the perfect narrative vehicle for a tale of seduction and resistance, virtue and vice – not to mention the opportunity to depict a beautiful half-naked woman – while also telling the story of a (male) hero resisting temptation.

The research I did almost a decade ago on Potiphar’s wife for a book on the women of the Hebrew Bible stopped in the 17th century. And while I do not know of any 21st century artistic or literary (re)interpretations of the ancient tale, I do know that its symbolism endures. Sadly, the resistance, the struggle, and the punishment of the victim instead of the accuser continue to ring true in the 21st century.