Catherine Yass

(British, b. 1963), Lighthouse (North north west, distant), 2011, Photographic transparency, lightbox, 50 ¾ x 40 ¾ in., The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art at Rollins College, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.11 © Catherine Yass. Image courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

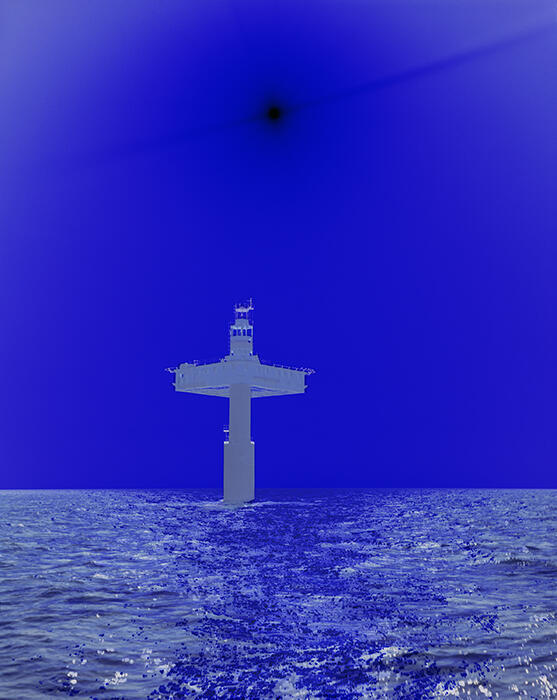

When you go to The Alfond Inn next time, I hope you will take a moment to look at this radiant work by British artist Catherine Yass (it is on view in the Library, on the left as you walk towards Hamilton’s Kitchen). The nuanced blue of the ocean, whitecaps and flickering reflections mixed into darker colors, occupies the lower quarter of the composition. Above, the water gives way to an intensely blue sky pierced only by a black sun. Against this expanse of sky – whose emptiness may be the very subject of the work – we see a silhouette rising from the ocean. We distinguish a rectangular building on a large platform supported by a very tall and seemingly too small single pillar. The structure, difficult to identify at first, is the Royal Sovereign Lighthouse off the coast of East Sussex, England. It is a decidedly unusual lighthouse, fully automated since the 1990s and thus appearing abandoned, isolated in the middle of the ocean.

The photographic transparency lightbox in our collection is part of a series that was created in conjunction with, and complementing, Yass’s 2011 film Lighthouse. In the film, the lighthouse is shot from a variety of vantage points: from boat, helicopter and underwater; circling, turning and spiraling around it; from above and below. The result is a feeling of disorientation and displacement, a push and pull described by the artist as “a magnet or siren attracting you in, but also signaling dangerous waters.” The still compositions retain this disconcerting feeling of the film, partly through a special technique of superimposing positive and negative images. In our work, a photographic color transparency is laid over a blue negative transparency, the two images having been taken a few minutes apart. The superimposition makes the areas that reflect the light become vivid blue, while the sun becomes black. An image taken during the day becomes ghost-like and surreal in its coloring, disorienting us, fulfilling the artist’s aim to place her viewers “somewhere slightly different, either physically or somewhere in their mind.”

Yass often talks about photography as language, noting that in order to understand it, one needs to study it, to deconstruct and understand it. In order to do that, she has experimented with the “wrong” materials or chemicals; has shot under different light; has reversed the order of processes, and – as illustrated here – has superimposed positive and negative images. She also uses an old plate camera, “about the hardest thing to use on a boat: you can’t see through the viewfinder while you’re taking a photograph, and by the time you’ve set up the shot, the waves have moved and you’re in another place.” Effort pays off as the final image draws you in, revealing itself slowly, inviting discovery and offering a whole array of (ambiguous) emotions. Today, the single structure in the vast expanse of the ocean may be a somber reminder of the isolation and loneliness many of us feel. Yet it may also be a beacon of hope, emphasized by the soft, beautiful light it radiates when experienced in person.

Ena Heller, Ph.D.

Bruce A. Beal Director

See this work by Catherine Yass on our Collection page.