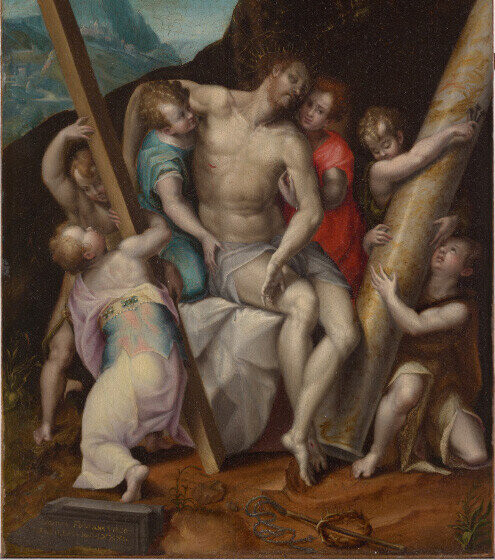

The Dead Christ with Symbols of the Passion, ca. 1581,

Oil, tempera on panel, 14 1/4 x 10 5/8 in. Gift of the late General and Mrs. John J. Carty, in memory of her brother, Thomas Russell, 1936.30

Outside of my bias of having been trained as an Italienist, The Dead Christ with Symbols of the Passion, is one of the most important Old Masters in our collection (as a mature work by one of the few female artists of the Italian Renaissance known to us today). It is one of less than a dozen by the artist in American museums. Moreover, it was the one painting in the collection of Rollins Museum of Art that I was rather familiar with before I started working here, having requested it for a 2011 exhibition at the Museum of Biblical Art. Upon my arrival at Rollins, and finally seeing the painting in person, I fully understood why the curators of that exhibition had been so distressed when the loan was not approved.

The Dead Christ with Symbols of the Passion

Up close, the painting – its diminutive size notwithstanding – has immense power. The skillful composition with Christ at the center, his body surrounded by six attending angels whose stances, each mirroring another, create a delicate ballet-like movement while directing our gaze in all the right places for deciphering the iconography: the dead Christ, the cross from which he had just been taken down, the column of the Flagellation. The diaphanous pinks and light yellows of the angels’ vestments, as well as the stronger red and blue directly flanking Christ, emphasize the pallor of his dead body as well as marking him as the center of the composition.

Lavinia Fontana (Italian, 1552-1614)

The Dead Christ with Symbols of the Passion, ca. 1581

Oil, tempera on panel, 14 1/4 x 10 5/8 in. Gift of the late General and Mrs. John J. Carty, in memory of her brother, Thomas Russell, 1936.30

And yet, for all the narrative episodes clearly referenced (see also the Crown of Thorns and whip in the foreground), this is not a narrative painting, but rather a meditative piece – an aid to prayer and contemplation. This is reinforced by the angel to the right of Christ, robed in red, the only figure in the painting looking straight out, inviting beholders to think about what they see, and contemplate the meaning. This, together with the small size of the painting, suggests that it was intended for private devotion, likely in the private residence of the (unfortunately unknown) wealthy patron for whom it was painted.

Artist Lavinia Fontana

Lavinia Fontana, born in the progressive city of Bologna, was one of the most successful and prolific women artists in sixteenth-century Europe. One of only a handful of known female artists working in sixteenth-century Italy, Lavinia Fontana received her initial training as a painter from her artist father, Prospero Fontana (1512–1597). Her father had her develop her artistic potential and obtain a humanistic education. He helped forge her public image as a refined and educated woman artist.

The odds that Lavinia Fontana had to overcome to become a successful artist in 16th century Italy were enormous. And it was harder still, as a woman, to receive commissions for religious art – considered of a higher order than other genres, such as portraiture. Indeed, we know that Lavinia enjoyed both private and public commissions for mythological and religious works, and quite a bit of recognition in her time.

Yet even an avowed admirer – and actual patron – of the painter wrote, a few short years after our painting was created,

“This excellent painter, to say the truth, in every way prevails above the condition of her sex.”

After her death, she descended into obscurity, to be rediscovered only in the late 20th century, with the ascent of feminist art history. Amazing, in this context, is the fact that The Dead Christ with Symbols of the Passion entered RMA’s collection as early as 1936, the first important Old Masters painting to do so. I so wish I could ask the donors if they knew what an exceptional painting they had and thank them for giving it to our museum.

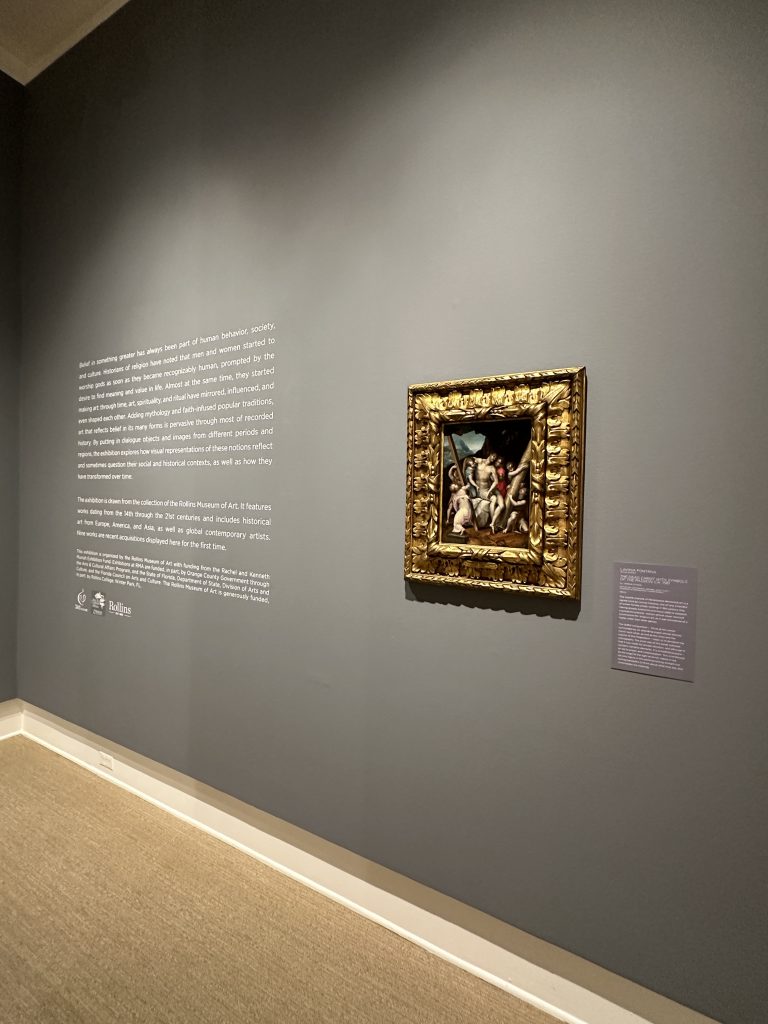

Visit Rollins Museum of Art to view The Dead Christ with Symbols of the Passion in Transformations: Spirituality, Ritual, and Society through May 12, 2024.

See a 360 degree virtual view of this exhibition.

Visit the Rollins Museum of Art Collections page for insights into more works from our permanent collection.