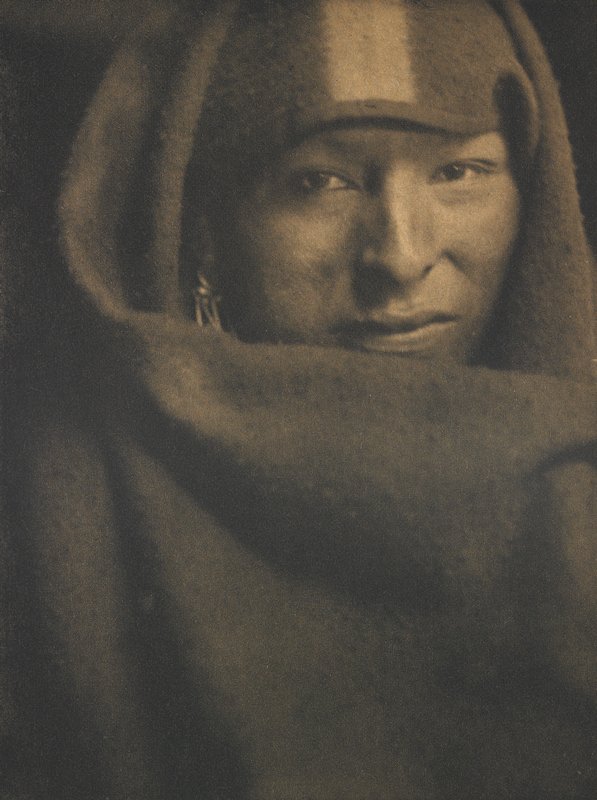

Gertrude Käsebier

(American, 1852–1934), The Red Man, 1898, Photogravure print. Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.13

I remember holding my first camera at age 5.

It was a film SLR—to this day I am still a purist—and from the first sound of the shutter release I was hooked. It was magic. It was science. It was a new way to see the world.

You can imagine my surprise when in my first year of college as an art major, I learned photography had inherited the stigma of being considered a lesser artistic medium. The advent of the Kodak handheld camera near the end of the nineteenth century had enabled amateurists to take part in the point-and-shoot photo revolution, leaving behind early experimentation with honing the medium’s artistic sensibilities. Due to its being a mechanical process with the capacity to reproduce the physical world, the artist’s hand no longer seemed part of the equation. Luckily, many photographers, among them Gertrude Käsebier, could see past this perceived limitation.

Science could be art—and it could be beautiful.

She was an early supporter of the Pictorialism movement, which sought to reverse the idea that photography could not be painterly. Joining the likes of Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen in the Photo Secession group, she adopted several older, labor-intensive printing styles, used alternative chemicals that yielded more nuanced tonal ranges, and reworked her plates with paintbrushes and other methods before printing. In the pictorialists’ hands, photography was art and being a photographer was a professionalized artistic craft.

We can see Käsebier’s painterly approach to photography in The Red Man (1898), a photogravure portrait of Takes Enemy, a Sioux performer in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. Käsebier’s choice to ink her plate with a brown, sepia tone was customary of pictorialists, as it presented a way of imbuing an image with emotion. The mischievously mysterious expression lends character and individuality to the sitter, setting it apart from the larger portfolio of images taken that day. While Käsebier’s photographs of the Wild West Sioux ensemble do not manage to sidestep the problematic romanticism of the “tamed and noble native” perpetuated through the medium, it does suggest a greater sense of agency was exchanged between photographer and subject.

Alexia Lobaina

Former Associate Curator of Education

To learn more about this work by Gertrude Käsebier, visit our Collection page.

This blog post was originally posted in 2020/2021.