Mortar from the Cell of Faliero, Doge’s Palace, Venice

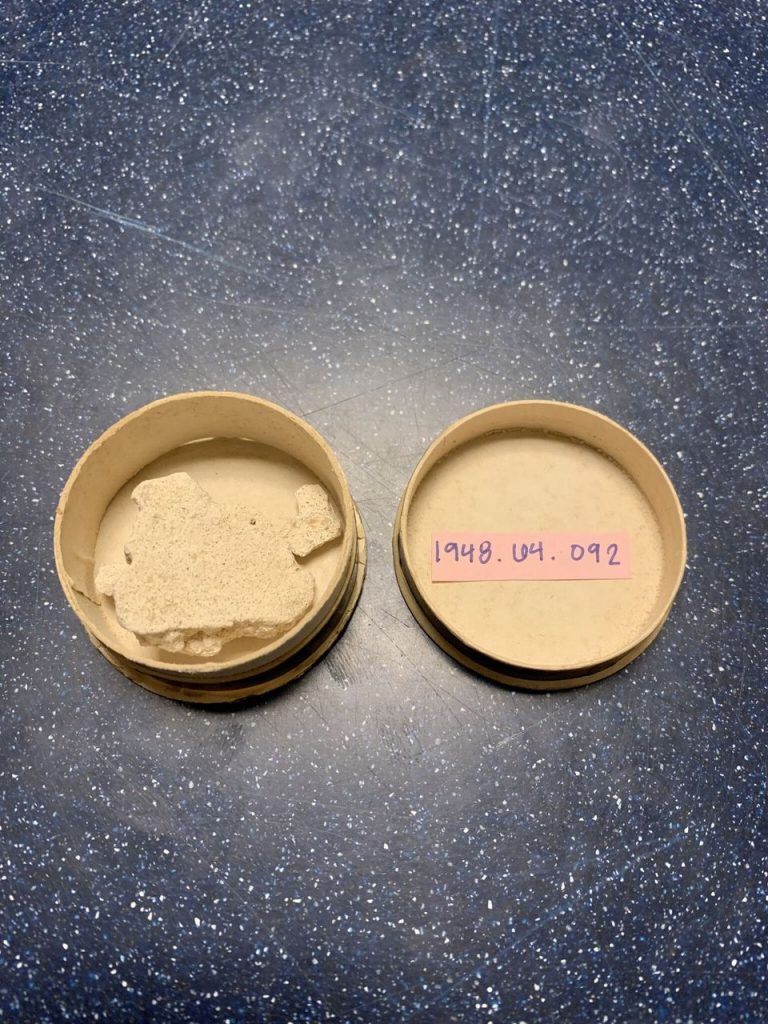

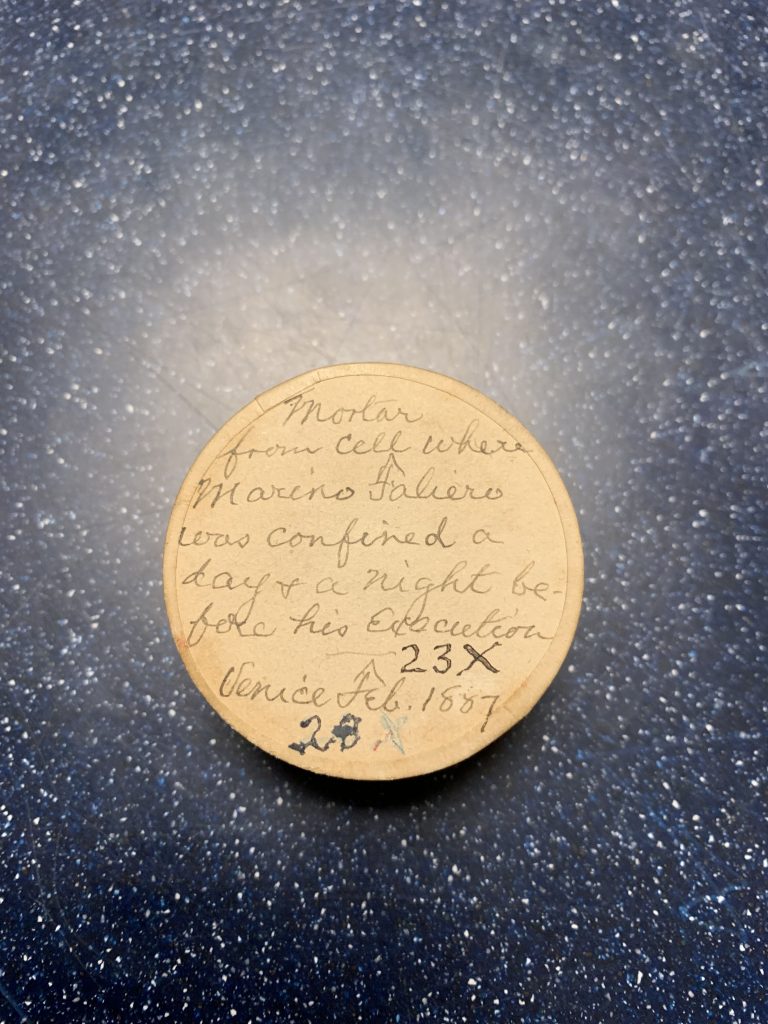

Canister with Reeve’s Handwritten Label

- Mortar from cell were Marino Faliero was confined a day and a night before his execution

- Date Acquired : February 1887

- Place Acquired : Doge’s Palace, St. MArk’s Square., Venice, Italy

- 45°43’7191″ N 12°33’459″ E

- BM# 1948.64.092

This object is mortar from the cell where 14th century Venetian Doge Marino Faliero was imprisoned before his execution. General McCormick Reeve obtained this mortar from the Doge’s Palace in February of 1887 when it the building was being used for the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, one of the oldest public libraries in Venice.

Marino Faliero was a military and naval commander who was appointed the 55th Doge of Venice in 1354. He also had experience as a governor of provinces. Faliero had previous political experience as an ambassador to the papal court at Avingon, France and as a member of the Council of Ten, a major governing body of Venice (Cavendish, 2005).At the time his election, the people of the Republic of Venice were unhappy with oligarchy government of aristocrats since the defeat by the Republic of Genoa at the Battle of Portolungo during the Third Venetian-Genoese War. In April of 1355. Faliero attempted to organize a coup d’etat in order to overthrow the aristocrats in power after his wife was insulted by Michele Steno, an aristocrat. Tales of an attack by a Genoese War Fleet on April 15th were spread in order to distract from Marino Faliero’s band of armed men killing as many nobles as they could. Faliero was then to named Prince of Venice. Faliero’s plot was poorly organized and was quickly foiled by the Council of Ten. All of the members involved in the plot were arrested (Cavendish 2005). Faliero was held in a prison cell in the Doge’s Palace the day before he was executed. On April 17th Faliero died on the steps of the Doge’s Palace in St. Marks Square, Venice.

The history of the Doge’s Palace begins in 810 when Doge Agnello Paticipazio ordered ducal palace to be built for the Republic of Venice in St. Mark’s Square. The original building burnt down in the 10th century which lead to Doge Sebastian Ziani to rebuild the palace as a fortress with Byzantine-Venetian architecture. Two new buildings were added to palace. One overlooked the Piazetta which housed courts and legal institutions. The other Faced St. Mark’s Basin to house government institutions (Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, 1).These additions defined a new look for St. Mark’s Square. Political changes in 1297 century led to another remodel to fit a bigger government (Hurst, 2015). In 1340 a gothic style portion was added to the structure under Doge Bartolomeo Gradengio. The gothic palace would have been the one Doge Marino Faliero lived, worked, and died in during his political career in 1354. The Doge’s Palace was remodeled several times after his death. Over the next few centuries the Doge’s Palace continued to house the Venetian government until 1797 when Venice was ruled by the French. In 1866 Venice became a part of Italy. The Italian government restored the building in the 19th century. The Doge’s Palace evolved into its current purpose in 1923, a museum (Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, 2). Since 1996 the Doge’s Palace has been a member of the Venetian museums network and under the direction of the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia since 2008.

Much of Venice’s historical buildings are built using brick lined with lime mortar. Lime mortar has breathability that can withstand the movement of the marshy foundations due to the gradual rise in sea water level (University of Mary Washington, 2008). The sea water would also deteriorate buildings, so most buildings would have to be re-plastered over time. The mortar used here is most likely Marmorino Plaster. This lime based plaster was first known to be used in the 1st Century. Roman architect Vitruvius denotes its use in his book written between 30 and 15 B.C.E. Marmorino Plaster became extremely popular in Venice during the 15th century when Vitruvius’ writings were rediscovered. Marimono plaster is made using calcium oxide (Meoded Paint & Plaster, 2017), crushed marble, and a lime putty. This mortar was most likely what General McCormick Reeve obtained in February of 1887.

For Further Reading

- Cavendish, Richard. 2005. “Execution of Marin Falier, doge of Venice: April 18th, 1355.” History Today, 53. Gale Academic OneFile.

- Chirkova, Aleksandra V., Daria A. Ageeva, and Evgeny A. Khvalkov. 2018. “The Relations of the Republic of Venice and the Marquises D’Este in the Mid-Fourteenth to Mid-Fifteenth Century Based on the Lettere Ducali from the Western European Section of the Historical Archive.” St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis.

- Contarini, Gasparo, and Lewis Lewkenor. 1599. The Commonvvealth and Gouernment of Venice. Written by the Cardinall Gasper Contareno, and Translated out of Italian into English, by Lewes Lewkenor Esquire. With Sundry Other Collections, Annexed by the Translator for the More Cleere and Exact Satisfaction of the Reader. With a Short Chronicle in the End, of the Liues and Raignes of the Venetian Dukes, from the Very Beginninges of Their Citie. London: Imprinted by Iohn Windet for Edmund Mattes, and are to be sold at his shop, at the signe of the Hand and Plow in Fleetstreet.

- Grignola, Antonella (1999). The Doges of Venice. Venice: Demetra.

- Howard, Deborah, and Sarah Quill. 2017. The Architectural History of Venice. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hurst, Ellen. 2015. “Palazzo Ducale.” Smarthistory. https://smarthistory.org/palazzo-ducale/.

- Lane, Frederic Chapin. 1973. “Venice, a Maritime Republic.” Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- “MARINO FALIERO.” 1888. Littell’s Living Age (1844-1896) 177, no. 2290: 400.

- Molmenti, Pompeo, and Horatio F. Brown. 1906. “Venice : Its Individual Growth from the Earliest Beginnings to the Fall of the Republic.” Chicago : London : Bergamo: A.C. McClurg ; John Murray ; Istituto Italiano.

- Nowrich, John Julius (2003) [1977]. A History of Venice. London: Penguin.

- “The Doge’s Palace.” Palazzo Ducale. Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. https://palazzoducale.visitmuve.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Guida-Ducale-ENG.pdf.