Eucalyptus Pods, Chapultepec, Mexico

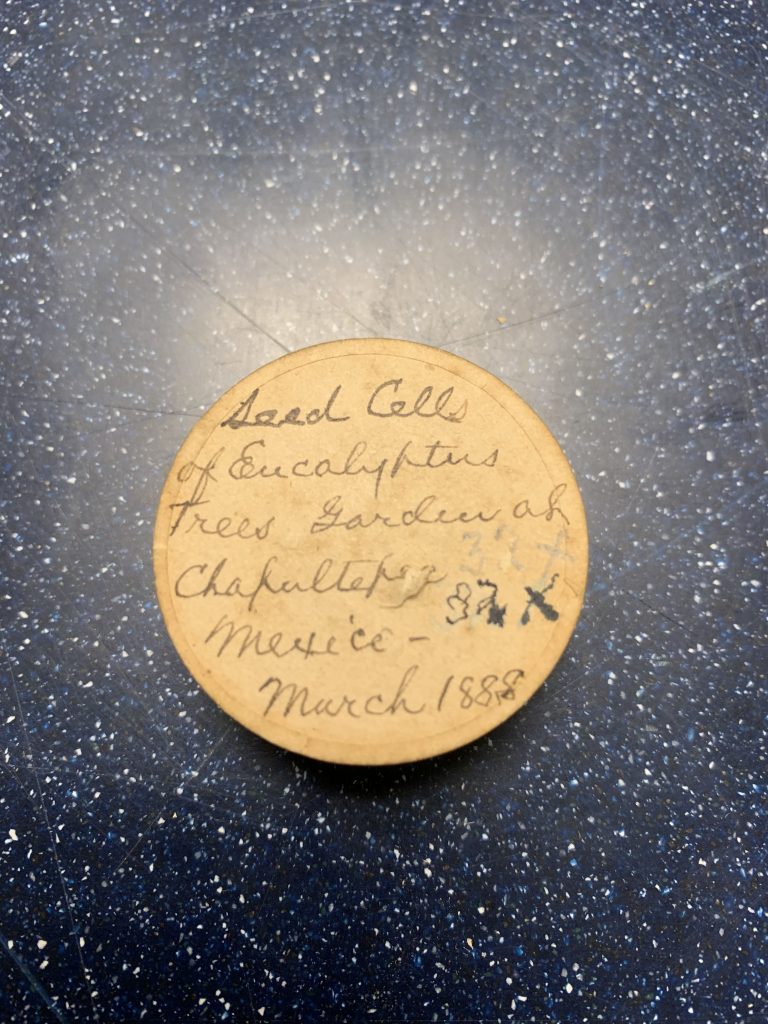

Canister with Reeve’s Handwritten Label

- Seed Cells of Eucalyptus Trees

- Garden of Chapultepec Mexico 19.41306°N 99.19778°W

- Acquired March 1888

- BM# 1948.64.105

General McCormick Reeve obtained these eucalyptus seeds in Chapultepec, Mexico in 1888. Eucalyptus was commonly used to ward off bugs and the diseases they might carry, as a source of wood, and as a decoration.

Eucalyptus has a long history of use ranging from medicine to warding off disease-carrying bugs. Due to these qualities, Reeve likely recognized their importance and kept the pods as keepsakes. The pods are no longer a vibrant color, but rather are feint and beige. Their shape is somewhat pyramidal with a rough texture.

Reeve visited the Garden or Chapultepec in 1888. During his visit, Reeve collected these eucalyptus seed pods, which were likely pulled from a nearby tree as the pods hang in clusters on tree branches.

As mentioned previously, eucalyptus has been utilized in numerous manners throughout history. The earliest being its use as an anti-inflammatory medicine, meaning it reduces pain and swelling (Weule 2018). In addition, eucalyptus is a fast growing tree, making it a fast source of wood (Midgley, Eldridge, and Doran 1989, 299). Others enjoyed the tree’s ability to drain marshes, which lowers the amount of mosquitos and the risk of malaria (Mahasveta 1983, 1380). Eucalyptus further serves as insect repellent due to the unique scent it produces that drives off bugs (Mahasveta 1983 1380). This variety of uses resulted in the spread of the tree across the globe.

The park of Chapultepec in Mexico was originally founded as a location for the Aztec elite (Arredondo 1976, 558). In its original form, the park contained a zoo and an assortment of exotic trees and plants. In the present, the only supposed original structure is Montezuma’s bath. During the colonial period, however, this location was turned into a fortress at the hands of Viceroy Galvez. In 1847 US marine forces opened fire on the fortress (the Hall of Montezuma), which was protected by the cadets within (Arredondo 1976, 558). However, this victory was not long lasting, with the French taking control of the location in 1863. During French control, Maximilian of Hapsburg added to the zoo, introduced lakes, created a large pathway connecting the park to the city, and planted several European species of plants and trees (this is likely when eucalyptus was introduced to the park) (Arredondo 1976, 558). After the death of Maximilian by firing squad in 1867, the French lost control of the castle (O’Connor 2018). It was then utilized as a presidential office until 1934 when the President decided to turn it into a public facing museum focused on the history of the city. The location has since undergone renovations to increase the size, functionality, and overall beauty of the park (Arredondo 1976, 559).

For Further Reading

- Akhtar et. al. 2016. “Medicinal Plants of the Australian Aboriginal Dharawal People Exhibiting Anti-Inflammatory Activity.” Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. doi: 10.1155/2016/2935403. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2016/2935403/

- Arredondo, Eliseo. 1976. “Ever Green Grows Chapultepec Park.” Landscape Architecture 66, no. 6: 558-59. www.jstor.org/stable/44664270.

- Bently, Robert. 1874. “On the Characters, Properties, and Uses of Eucalyptus Globulus and Other Species of Eucalyptus.” 3-17. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044107243750.

- O’Connor, William. 2018. “Chapultepec, the Mexican Castle That Drove a Belgia Princess to Madness and an Austrian Archduke to the Firing Squad.” Daily Best. Last Updated Jul. 23, 2019. https://www.thedailybeast.com/chapultepec-the-mexican-castle-that-drove-a-belgian-princess-to-madness-and-an-austrian-archduke-to-the-firing-squad

- Mahasveta Devi. 1983. “Eucalyptus: Why?” Economic and Political Weekly 18, no. 32: 1379-381. www.jstor.org/stable/4372377.

- M. Fladung et. al. 2015. “Differentiation of six Eucalyptus trees grown in Mexico by ITS and six chloroplast barcoding markers.” Silvae Genetica. 64, no. 3: 121-130. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294736743_Differentiation_of_six_Eucalyptus_trees_grown_in_Mexico_by_ITS_and_six_chloroplast_barcoding_markers

- Midgley, S. J., K. G. Eldridge, and J. C. Doran. 1989. “Genetic Resources of Eucalyptus Camaldulensis.” The Commonwealth Forestry Review 68, no. 4 (217): 295-308. www.jstor.org/stable/42608477.

- Stein, Achva Benzinberg, and Jacqueline Claire Moxley. 1992. “In Defense of the Nonnative: The Case of the Eucalyptus.” Landscape Journal 11, no. 1: 35-50. www.jstor.org/stable/43323057.

- Weule, Genelle. 2018. “Eucalypts: 10 things you may not know about an iconic Australian.” ABC Science. Jan. 27, 2018. https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2018-01-26/eucalyptus-trees-an-iconic-australian/9330782