Mortar Fragment from Girolomo Savonarola’s Cell in San Marco, Florence, Italy

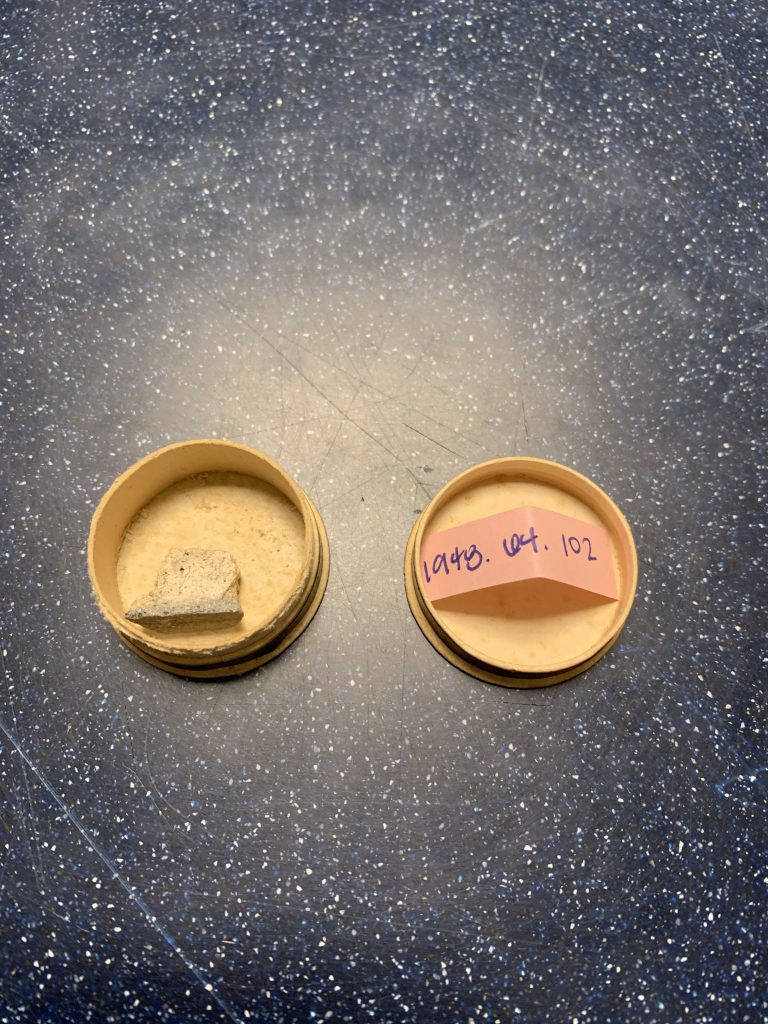

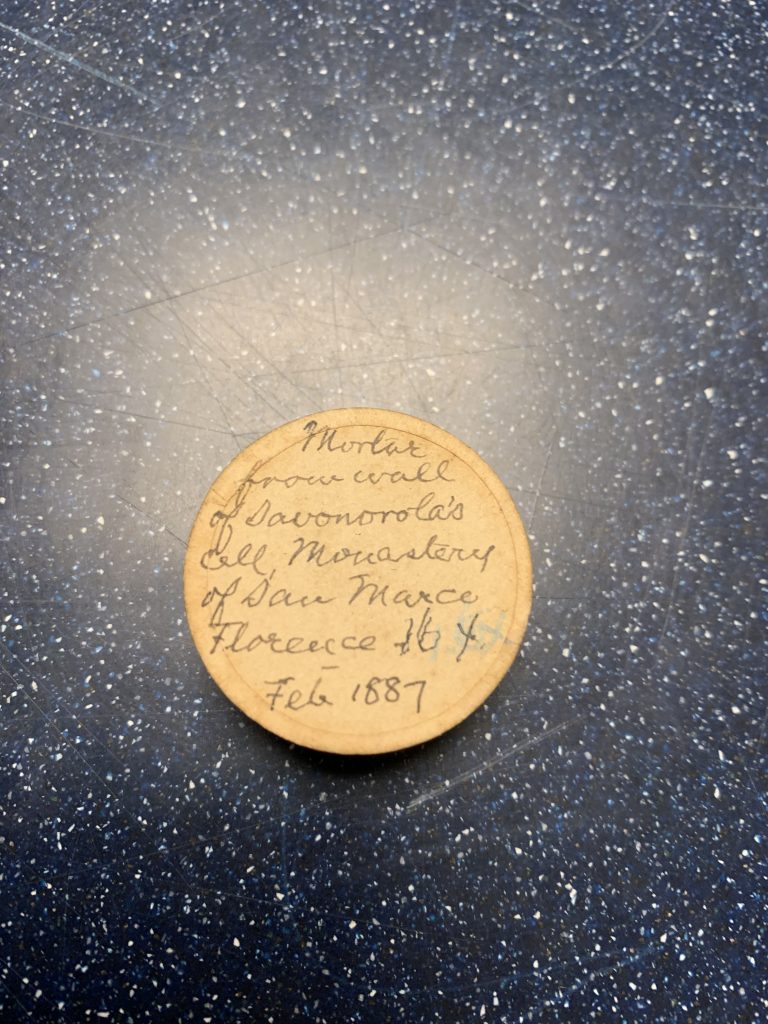

Canister with Reeve’s Handwritten Label

- Mortar Fragment from Girolomo Savonarolla’s cell in the Monastery of San Marco

- Florence, Italy

- Acquired February 8th, 1887

- BM# 1948.64.102

Container 102 holds a fragment of mortar from the Monastery of San Marco in the cell of Girolamo Savonorola. The fragment was collected as part of an unrecorded trip through Venice, Florence, Rome, and Pompeii in 1887 by Charles McCormick Reeve. The composition of the mortar is a mixture of water, soil, and lime, and it was used in medieval buildings for holding together large blocks of masonry (Graymont n.d., para. 1-4).

The Monastery of San Marco was originally a small building in the Piazza San Marco renovated by an order of Silvestrian monks into a monastery, with the addition of a modest church; the Silvestrians inhabited the building for over a century, but after their morals deteriorated and complaints were lodged, the then-dilapidated building was granted to a more worthy brethren. The Dominicans, monks devoted to Christian scholarship and encouragement of Christian art and literature, were favored by Cosimo De Medici, and they were granted the monastery. Cosimo then commissioned an expansion and renovation of the building by Michelozzo in 1437, and the new library became the first public library in Florence (Godkin 1887, 16-18; “San Marco Museum” n.d., para. 1). Artist Fra’ Angelico decorated the walls of the monastery, and it now houses the largest collection of his art in the world (“Convent of San Marco” n.d., para 1).

The monastery was also home to Dominican monk Girolamo Savonorola. Savonorola dominated Florentine society from AD 1494-1498, reshaping its political landscape and moral philosophy and opposing the powerful Medici family (Martines 2006, 19). He preached about the need for repentance, and divine grace, and thought art and worldliness encouraged unbelief. In the face of the Renaissance, and its connections to classical antiquity and paganism, he believed the apocalypse was drawing near, and Florence could become a New Jerusalem if purified of its sins (Weinstein 2011, 14-19). He advocated for the burning of “vanities” like sculptures, paintings, literature, and even perfume and exotic drapings (Weinstein 2011, 239). However, after his excommunication, the city eventually turned on him, and he was tortured into confessing his prophecies were lies, before he was hanged, and burned (Godkin 1887, 103-110). Now, a portrait, a procession banner, some of his items, and a marble monument erected in 1873 sit in the monastery within his former cells, located in the upstairs of the complex above the entrance (Williams & Dixon 2018, 279; Bekker 2020).

Further Reading

- Bekker, Henk. “Floor Plan Of San Marco Museum.” European Traveler, April 10, 2020. https://www.european-traveler.com/italy/visit-the-san-marco-museum-in-florence-to-see-fra-angelico-paintings/attachment/san-marco-museum-map/ .

- Binding, Gunther. Medieval Building Techniques. Stroud, England: Tempus, 2004.

- “Convent of San Marco.” The Museums of Florence. Hidden Italy. Accessed June 2, 2020. http://www.museumsinflorence.com/musei/museum_of_san_marco.html .

- Godkin, G. S. The Monastery of San Marco. Italy: Printed by G. Barbèra, 1887, 1887.

- Graymont. n.d. “History of Lime in Mortar.” Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.graymont.com/en/markets/building-construction/mortar/history-lime-mortar .

- Iturgaiz, Domingo. “Dominican Order.” Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 2 Jun. 2020. https://www-oxfordartonline-com.ezproxy.rollins.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000023204 .

- Martines, Lauro. Fire in the City: Savonarola and the Struggle for the Soul of Renaissance Florence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Reeve, Charles McCormick. How We Went and What We Saw. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1891.

- “San Marco Museum.” Florence Art Museums, May 14, 2020. https://www.florenceartmuseums.com/san-marco-museum/ .

- Scudieri, Magnolia. Museum of San Marco: The Official Guide. Italy: Giunti, 2014.

- Strathern, Paul. Death in Florence: the Medici, Savonarola, and the Battle for the Soul of a Renaissance City. New York, NY: Pegasus Books, 2016.

- Weinstein, Donald. 2011. Savonarola: The Rise and Fall of a Renaissance Prophet. New Haven: Yale University Press. Accessed June 2, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Williams, Nicola, and Belinda Dixon. Florence & Tuscany. 9th ed. Travel Guide. Libby. Footscray, Victoria: Lonely Planet Publications, 2018. https://libbyapp.com.