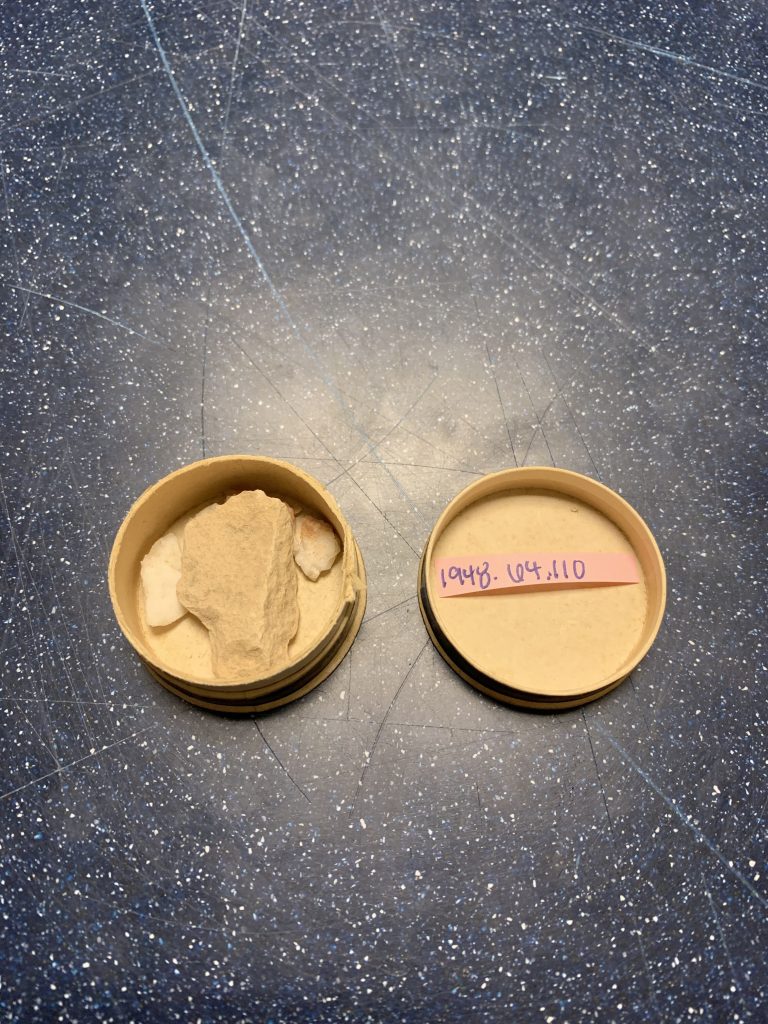

- Six pieces of alabaster acquired from the Tomb for the Mamelukes, Cairo, Egypt, situated beneath the Mosque of Muhammad Ali, 30.0287° N, 31.2599° E

- Acquired on January 18th, 1889

- BM# 1948.64.110

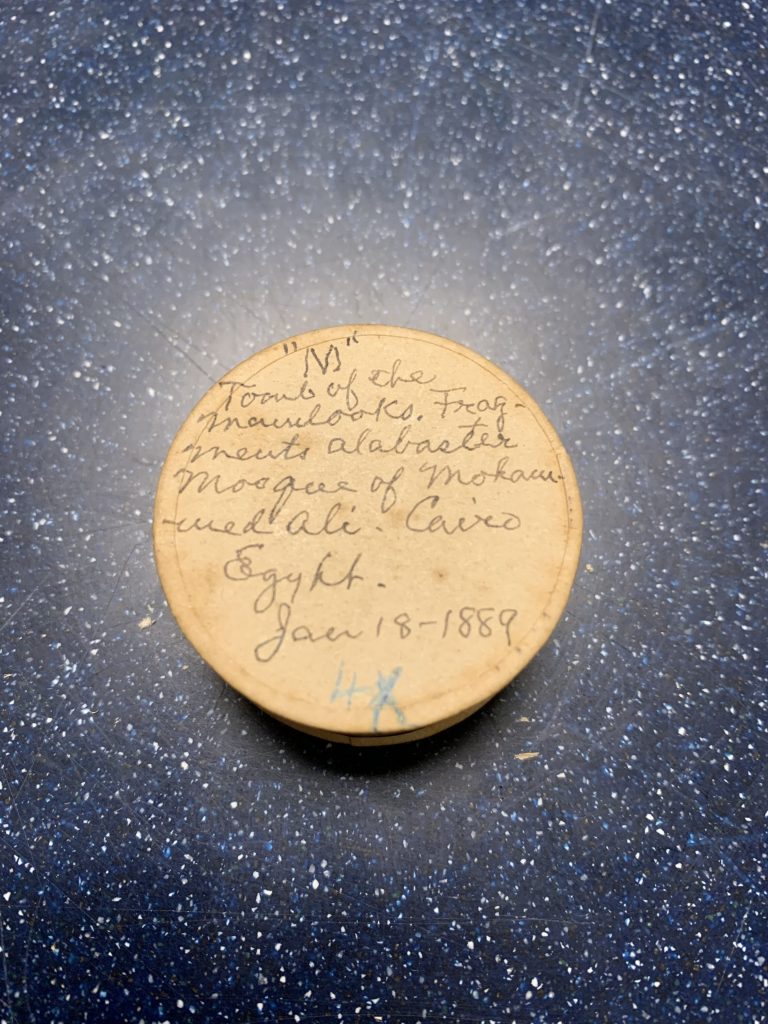

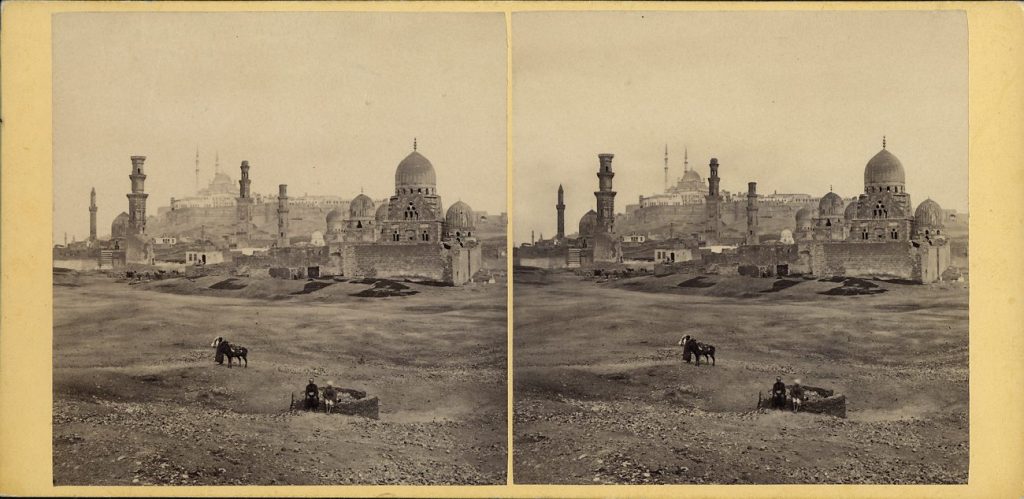

General Reeve was what archaeologists now call a chipper—someone who takes small pieces of monuments as they visit them to add to their personal collection. Reeve chipped away alabaster from the Tomb of the Mamelukes during his tour of Egypt, Syria and the Aegean Islands in 1889, a trip he organized with his close family and friends. The group left from Minneapolis and began their tour with a brief stop in Alexandria before traveling to Cairo. Reeve described the Islamic monuments of Cairo in his book How We Went and What We Saw, stating, “the first and greatest wonder of the world; incomparable; mysteries as well as marvels in stone” (Reeve, 1890, 47). Furthermore, while standing at the Tomb of the Mamelukes, situated at the foot of the hill holding Muhammad Ali’s mosque, Reeve described the mosque’s looming figure: “you are beneath the shadow of the walls of the world-renowned mosque of Mohammed Ali” (Reeve, 1890, 46). Mohammad Ali’s mosque could be clearly seen from all surrounding areas due to its situation on the hill, and therefore the Tomb of the Mamelukes was one of many monuments laying in its shadow.

https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/2aaa86a6-d9f7-4e8e-b368-692215691454

Cairo is home to many significant Islamic mosques and tombs, the earliest of which dates to the 7th century AD (Al-Asad, 1992, 39). The Mamelukes served the Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt from the beginning of its reign in the 13thcentury. Al-Sālih Najm al-Din Ayyūb was the last ruler of the Ayyubid dynasty, from 1240-49. During his reign, he introduced a new way of leading, with increased dependence on the army at his service, and he became the first Ayyubid ruler to fill his army with, and depend mostly on, Mamelukes (Levanoni, 1990, 121-4). The Mameluke army gained power through their increased role in Al-Sālih’s Ayyub’s rule and after his death, fought the French invaders, led By Louis IX, for the Egyptian throne. The Mamelukes won against the French in 1249 and were the ruling dynasty of Egypt from 1250-1517 (Levanoni, 1990, 130-7). The Mameluke dynasty was the predecessor of Muhammad Ali’s dynasty, also known as the Alawiyya dynasty or the Khedival dynasty (Williams, 2001/02, 591; Rogers, Rogers, and Seymour, 1880, 202).

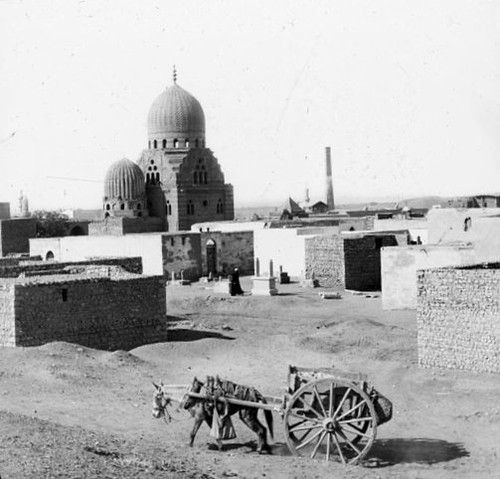

During their reign, the Mamelukes worked to protect and glorify their city, extending the boundaries of the city to include one of Cairo’s oldest Islamic monuments, the mosque of Ahmad ibn Tulun (Williams, 2001/02, 191). The preservation of significant Islamic monuments, as well as other monuments of their city, was very important to them.

https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/4bd29eb7-64a5-4074-98e5-a812848fd8c3

Alabaster is a softer stone, often used in carving. It was frequently used in Egyptian art and has been quarried since the 1st century AD. Both the Tomb of the Mamelukes and the Citadel of the Mosque of Mohammad Ali are made from alabaster (Rogers, Rogers, Seymour, 1880, 204). The Tomb of the Mamelukes is quickly falling to decay, and in 1880 when Edward Thomas Rogers wrote about the Mosque Tombs in Cairo, he stated, “many of these buildings are remarkable for beauty of design and careful workmanship, but their history is unknown” (Rogers, Rogers, Seymour, 1880, 201).

https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/530f84b8-60ad-4a61-8568-f72284cc1377

For Further Reading

- Al-Asad, Mohammad. 1992. “The Mosque of Muhammad ‘Ali in Cairo.” Muqarnas 9: 39-55.

- Behrens-Abouseif, D. 2007. “The madrasa and Friday mosque of Sultan Hasan (1356-63).” In Cairo of the Mamluks : A History of the Architecture and its Culture. 201–213. London: I.B. Tauris.

- “Egyptian Alabaster.” 2016. CAMEO. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. http://cameo.mfa.org/wiki/Egyptian_alabaster

- Levanoni, Amalia. 1990. “The Mamluks’ Ascent to Power in Egypt.” Studia Islamica 72: 121-144.

- Reeve, Charles McCormick. 1890. “Cairo.” In How We Went and What We Saw, written by Charles McCormick Reeve, 38-47. New York: Knickerbocker Press.

- Rogers, Edward Thomas, Mary Eliza Rogers and George L. Seymour. 1880. “Cemeteries and Mosque Tombs, Cairo.” The Art Journal (1975-1887) 6: 201-204.

- Williams, Caroline. 2001/2002. “Islamic Cairo: A Past Imperiled.” The Massachusetts Review 42:4: 591-608.

- Williams, Caroline H. 2008. Islamic monuments in Cairo the practical guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10409523.

- Williams, John Alden. 1984. “Urbanization and Monument Construction in Mamluk Cairo.” Muqarnas 2: 33-45.