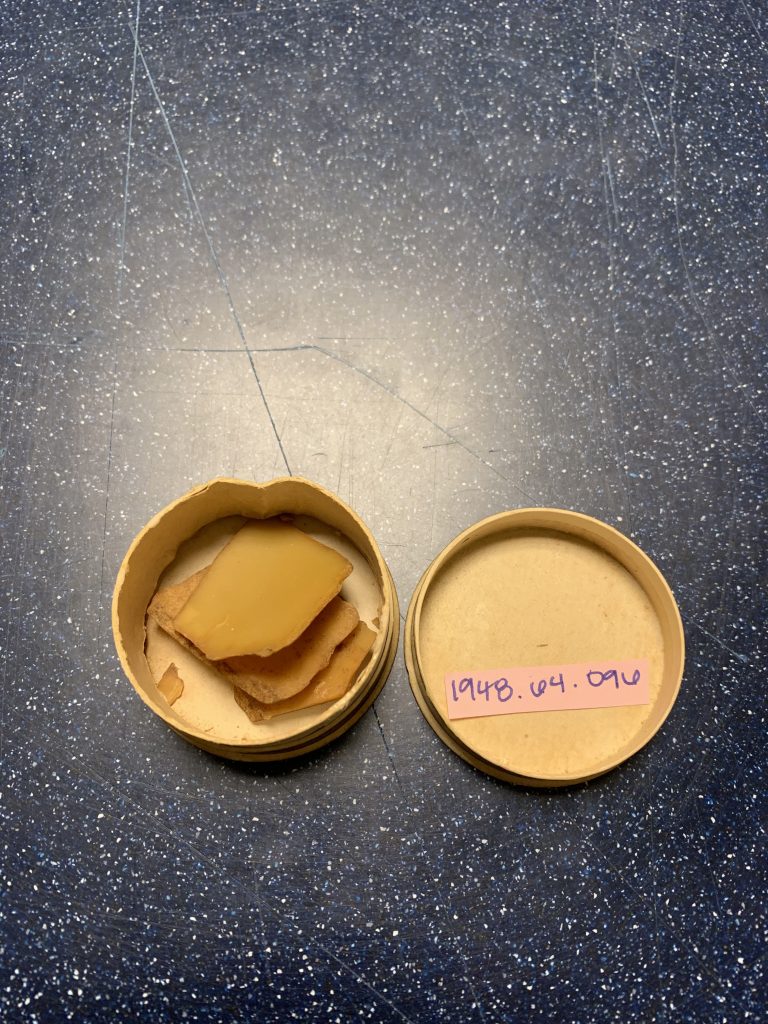

Wax Scales from the Candles in the Tomb of Saladin

Canister with Reeve’s Handwritten Label

- Tomb of Saladin in Damascus, Syria (33.5122° N, 36.3060° E)

- Acquired in 1889

- BM# 1948.64.096

Container containing candle slices that were cut, which are yellow/orange in color. From the Mausoleum of Saladin in Syria that was created and opened in 1196. Saladin was a great sultan that ruled Northern Africa in the 12th century. His burial followed the ways of Islamic religious and burial practices, which looked to connect morals and the deceased with olfactory smells and auras. As such, these candles were a crucial part of his tomb, as were specific Koran and architectural, present in this sacred building.

The scales from the candle from the Mausoleum of Saladin which sits next to the Great Mosque, a building that particularly piqued Reeve’s interest. To enter the tomb of Saladin it is required that a person pay a hefty fee, wear sacred slippers and be accompanied by a “cavass” or armed retainer (Reeve 1891, 259). When inside the tomb, Reeve stated that the tomb is surrounded by magnificent blue tiles from floor to ceiling on the walls, with aspects of the Koran present on black velvet embroidered in silver at the head of the tomb (Reeve 1891, 260). He also noted that huge wax candles were in each corner of the tomb which were to be lit only at great religious festivals (Reeve 1891). Reeve left the eternal city of Damascus, and its great past, with a feeling that these religious structures were quite dreary and not dramatic enough for the deceased residing in them, along with his pieces of candle from the tomb he visited.

These scales are the wax from the large candles that graced the four corners of the tomb of Saladin. Candles and incense are frequently found in these Islamic burial places, especially those of sultans such as Saladin. These candles can be as tall as men, weighing 20 kantar approximately 2,486 pounds, such as in other extant sultans’ tombs (Ergin 2014, 82). Reeve described the candles at the Tomb of Saladin as “huge” and yellow/orange in color (Reeve 1891, 263.). Islamic religion and burial practices place an emphasis on the olfactory elements in the sacred space, and the relationship it creates between the living and the deceased (Ergin 2014, 84). There is a “multi-sensorial message of the divine” communicated to worshippers and visitors in mosques and mausolea (Ergin 2014, 84). There are many measures taken to create a pleasant-smelling environment within a place of prayer to link heaven and earth. This “active agent of divine presence” is what allows metals to access the divine realm otherwise closed off to them, and provide sacrificial offering to gods or past rulers (Ergin 2014, 85).

The Mausoleum of Saladin is the tomb of a powerful Islamic military leader who ruled as sultan over Syria, Egypt and North Africa from AD 1174-1193 (Novak 2012, 44). He had a great military, political and sovereign career in the time of his power and influence, which is why Saladin’s tomb, is known to Muslims as a holy site. It was constructed in 1196, after being ordered to be built as sacred space by Saladin’s sons three years after his death. At the time of Saladin’s death, his only possessions were one piece of gold and forty pieces of silver (Novak 2012, 45). He had given away his great wealth to his poor subjects, leaving nothing to pay for his funeral (Novak 2012, 45). Due to his dutiful sultan accomplishments and care for the people of his regime, his tomb was decorated with great imagery and architecture, in addition to being of traditional Islamic burial practices.

Architecture in this area of Syria is Damascene Ayyubid. At this time, the creation of a square chamber with ablaq walls with rows of alternating light and dark stones and four arches capped by a “cupola” or small dome was very common (Walker 2004). Movement from the square room to the circular dome containing Saladin’s remains, is achieved by a transitional drum like hall in two places of connection, one an octagon and one a 16-sided polygon. The interior of the tomb chamber is paneled with blue and green Ottoman tiles, “qashani”, a mosaic decorative technique that can be seen in the stone-paste floral and geometric designs above the arches (Walker 2004). In the center of this space, there is a wooden sarcophagus with Saladin’s remains inside. It is decorated with geometric and astral patterns as well as floral and vegetal motifs that are similar to the blue and green tile details inside the tomb.

In addition to these decorative elements, large candles were placed in the tomb when it was created in 1196 in the four corners of the room containing the sarcophagus. They were part of the multisensorial connection between mortals and the great sultan Saladin. The candles added to the sacred environment he was placed in for eternity by his children so that he could be worshipped and given sacrifice because of the believed connection between mortals and the divine with a pleasant olfactory element (Ergin 2014, 88). The candles are one of the more prominent elements in Saladin’s tomb, along with the decorative architecture discussed above and elements of the Koran. These pieces were later taken as a token by General Reeve during his expedition in1891 many centuries after their origin.

Further Reading

Reeve, Charles M. “How We Went and What We Saw: A Flying Trip Through Egypt, Syria and the Aegean Islands.” G. P. Putnam Sons, 1891: 226-272.

Ergin, Nina. “The Fragrance of the Divine: Ottoman Incense Burners and Their Context.” The Art Bulletin 96, no. 1 (2014): 70-97. Accessed April 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/43947707.

Novak, Sarah. “Saladin’s Legacy.” Calliope 22, no. 7 (2012): 44-49.

Walker, Bethany J. “Commemorating the Sacred Spaces of the Past: The Mamluks and the Umayyad Mosque at Damascus.” Near Eastern Archaeology 67, no. 1 (2004): 26-39. Accessed April 6, 2020. doi:10.2307/4149989.

Briggs, Martin S. “The Architecture of Saladin and the Influence of the Crusades (A. D. 1171-1250).” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 38, no. 214 (1921): 10-20. Accessed April 5, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/861268.

Kinney, Ed. “The Umayyad Great Mosque in Damascus. (Timeless Roads of the Mideast & Mediterranean).” International Travel News 27, no. 6 (2002): 125.

Wien, Peter. “THE LONG AND INTRICATE FUNERAL OF YASIN AL-HASHIMI: PAN-ARABISM, CIVIL RELIGION, AND POPULAR NATIONALISM IN DAMASCUS, 1937.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 43, no. 2 (2011): 271-92.

Leiser, Gary. “The Endowment of the Al-Zahiriyya in Damascus.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 27, no. 1 (1984): 33-55.

Blair, Sheila, and Jonathan Bloom. “The Mirage of Islamic Art: Reflections on the Study of an Unwieldy Field.” The Art Bulletin 85, no. 1 (2003): 152-84.

“The History Of Islam: The Spread Of Islam And The Age Of Islamic Empires.” 2004, Understanding Islam and Muslim Traditions.