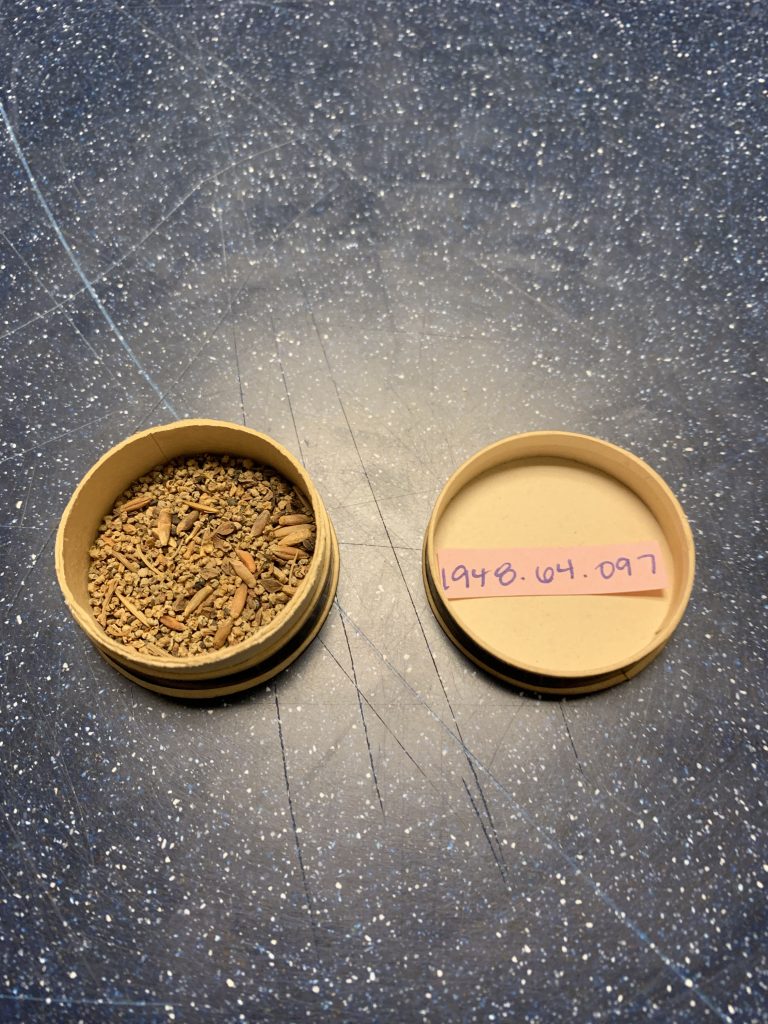

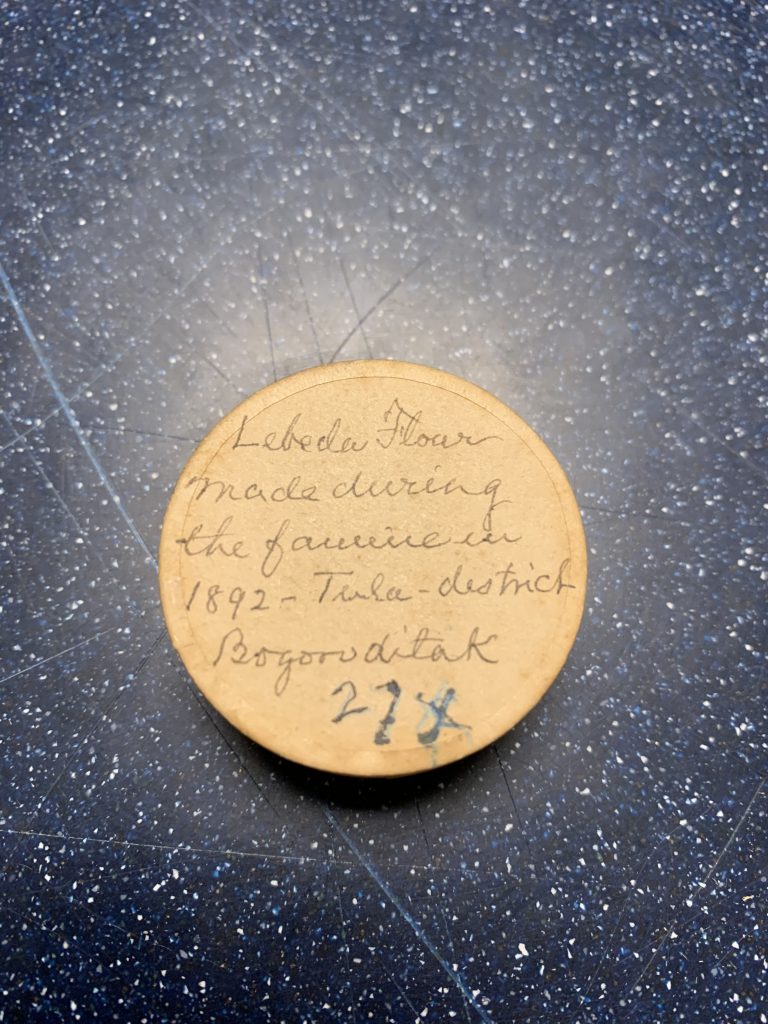

Lebeda Flour Mixture Used for Famine Bread during the Great Russian Famine, 1892

Canister with Reeve’s Handwritten Label

- Place Acquired: Bogoroditsk, Russia

- Date Acquired: 1892

- BM# 1948.64.097

This container holds raw organic material that is labeled as flour that was sent as relief from the United States to Russia at the time of the famine in 1892. For starving people consuming this raw and donated flour and “famine bread,” which is a mixture of moss, goosefoot, bark and husks, was their only aid. Minnesota sent a steamboat of this grain to Russia, after General Reeve was named the relief commissioner from Minnesota and Nebraska for the Great Famine of 1892.

The famine was the year after General Reeve was traveling on his expedition and expanding his collection of artifacts. However, at the time of the famine, he was residing in Minnesota and he owned a grain mill. General Reeve was elected representative to the Minnesota state legislature in 1891. Then in 1892 he was named the relief commissioner from Minnesota and Nebraska for the Great Famine of 1892, and was responsible for gathering grain to be sent to Russia. He acquired this material at this time, when the Missouri steamboat brought this famine bread to Russia.

At the end of the 19th century in Russia, there was an extensive grain market and crops were soldin huge bushels, making them a very competitive grain distributer. They focused on planting and harvesting winter and summer wheat, rye, barley, spelt, buckwheat, millet, peas, maize and oats (Simms 1982, 56). In the years before the famine, the crop yields were far lower than expected, specifically more than 20% lower than was tyoical in these provinces (Simms 1982, 57). During the time of the famine, starving people were consuming boiled weeds and handfuls of flour. Livestock was also depleted. There was an increased amount of dampness within the land, limiting the ability to keep a fire which led, in combination with the limited food supply, to the outbreak of typhoid (Queen 1955, 148)(Smith 1970, 146). The aid sent from the United States was the only real and stable source of food people were receiving (Queen 1955, 148). This food came in the form of this flour bread or “hunger bread,” being a mix of raw wild arroch, straw, bark, ground acorns, sand, and sometimes a little rye flour (Smith 1970).

Reeve obtained the lebedav flour from Bogoroditsk, a small administrative center of the Bogoroditsky District in Tula Oblast of Russia, located on the Upyorta River. The site was originally a wooden fort, which was demolished in AD 1770 in order to make room for the palace of the Bobrinsky family. The Tula district, where the famine occurred, is located southeast east of Moscow in the very heart of Russia. It stretches 500 miles in length from north to south along the Volga river region, and an equal distance radiance out east and west (Queen 1955, 142). During the time of the famine which began in 1892 and lasted until November 1893, harvest logs and census show that more than 20,000,000 people were residing there and that 13,728,000 needed assistance during this scarce time (Queen 1955, 143). In this area, grain was 75% of the Russian diet in 1891, and famine resulted from lack of harvest and a limited supply of food reserves from previous years.

The famine was a result of poor harvest and a lack of proper decisions made around the great grain market of Russia. In 1889, 1890, and 1891 the grain harvests were fifteen, five and twenty-six per cent below normal respectively, due to droughts in the Volga River region (Smith 1982). Further exacerbating the famine was the decision of the Russian Government to confiscate reserves in provinces to make huge grain exports, even during these lean years of 1889 and 1890. Thus, the famine was caused both by lack of grain and improper management of resources (Queen 1955, 143).

During the time of the Great Famine, America was Russia’s main competitor in the grain market. However, America displayed great friendship and aid in this time of need for Russia, after the New York Times reported this news of starvation across the Atlantic. The editor of the New York Times, W. C. Edgar, had come up with the idea of sending a cargo of flour to the famine sufferers (Queen 1955, 146). In addition to Edgar, the governor of Minnesota, W. R. Merriam got behind the movement and appointed a state committee with Edgar in charge, with subcommittees in every county to collect funds and food. In addition, Reeve who was elected representative to Minnesota state legislature in 1891, and then was named the relief commissioner from Minnesota and Nebraska in 1892. He was traveling to Russia a few months prior to the aid arriving on a ship, in March, and reported that he witnessed extreme widespread hunger and starvation (Levasseur 1892, 86). A large bulk of grain was gathered by these leaders and sent over to Russia on the Steamboat Missouri. This contribution was valued at more than $26,000 and there was 5,389,728 pounds of flour in total (Smith 1970, 149). The Russian government in turn was very grateful and the people of Russia were thankful to be able to fulfill their food needs for themselves and their livestock, which allowed the economy to return to its natural state shortly after.

Smith, Harold F. “Bread for the Russians William C. Edgar and the Relief Campaign of 1892.” Minnesota History 42, no. 2 (1970): 54-62. Accessed April 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/20178084

Simms, James Y. “The Crop Failure of 1891: Soil Exhaustion, Technological Backwardness, and Russia’s “Agrarian Crisis”.” Slavic Review 41, no. 2 (1982): 236-50. Accessed April 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/2496341.

Smith, Charles Emory. “The Famine in Russia.” The North American Review 154, no. 426 (1892): 541-51. Accessed April 7, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/25102370.

Queen, George S. “American Relief in the Russian Famine of 1891-1892.” The Russian Review 14, no. 2 (1955): 140-50.

Levasseur, E., and R. H. H. “The Russian Famine.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 55, no. 1 (1892): 80-87. Accessed April 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/2979394.

Eric M. Johnson. “Demographics, Inequality and Entitlements in the Russian Famine of 1891.” The Slavonic and East European Review 93, no. 1 (2015): 96-119. Accessed April 6, 2020. doi:10.5699/slaveasteurorev2.93.1.0096.

Hodgetts, E. A. Brayley. In the Track of the Russian Famine: The Personal Narrative of Journey through the Famine Districts of Russia. T. Fisher Unwin, 1892.

Strum, Harvey. “Pennsylvania and Irish Famine Relief, 1846–1847.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 81, no. 3 (2014): 277-99. Accessed April 6, 2020. doi:10.5325/pennhistory.81.3.0277.

Seyf, Ahmad. “Iran and the Great Famine, 1870-72.” Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 2 (2010): 289-306. Accessed April 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/20720663.

Hupy, Katherine L. American Famine Aid Campaign : Russian – American Relations at the Turn of the 19th Century, 1990.

Alexander Trapeznik. “Worker Unrest in Late Nineteenth-Century Russia: Tula, a Case-Study.” Social History 25, no. 1 (2000): 22-43. Accessed April 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4286607.

Hodgetts, E. A. Brayley. In the Track of the Russian Famine: The Personal Narrative of Journey through the Famine Districts of Russia. T. Fisher Unwin, 1892.