Famine Bread Baked on the Estate of A. Bobrinskaya during the Great Russian Famine

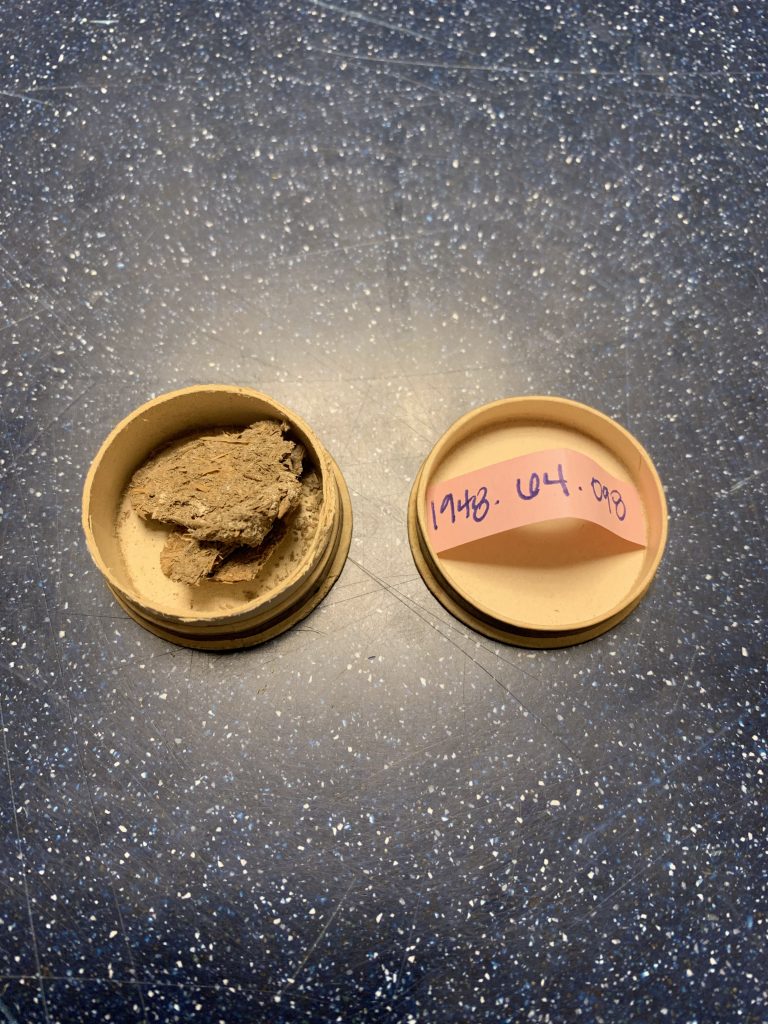

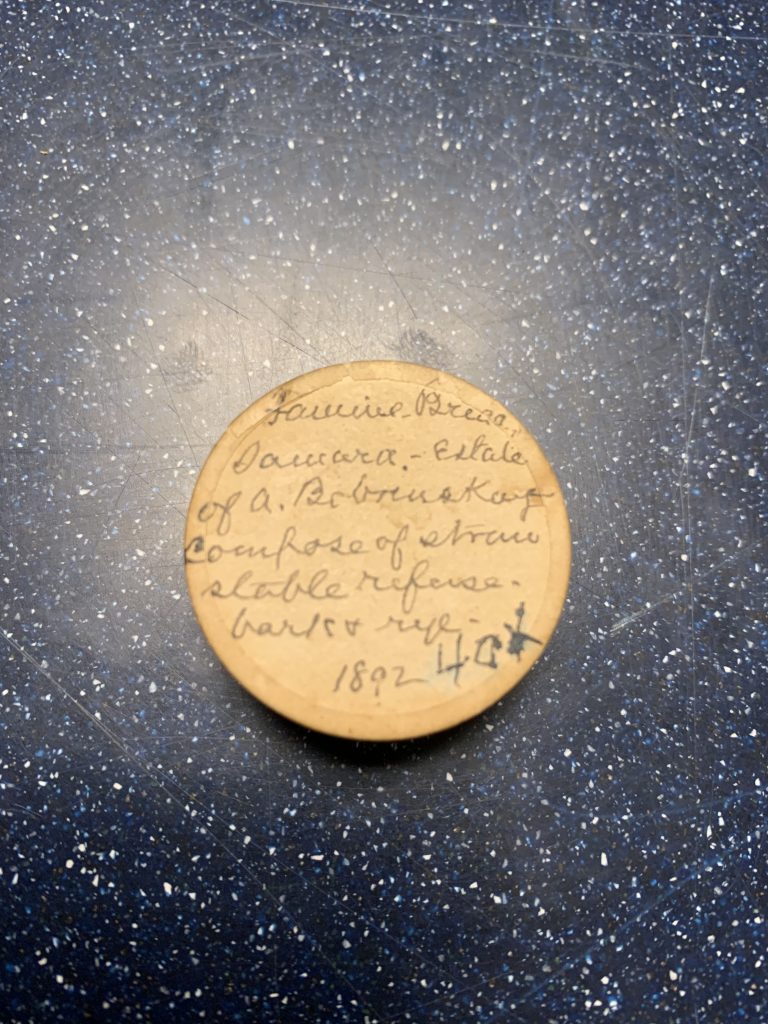

Canister with Reeve’s Handwritten Label

- From Samara, Russia

- Date Acquired 1892

- BM# 1948.64.098

General Reeve acquired this famine bread while fulfilling his duties as a Relief Commissioner in the 1891-1892 Russian Famine relief effort. Reeve was likely presented with famine bread from one of the most affected areas to demonstrate the need for aid. It is also possible he traveled to the area while overseeing the flour’s distribution and obtained it then.

After enduring poor harvests throughout the 1880s, Russian farmers were hit with a devastating drought the summer of 1891 that left “fourteen to sixteen million” Russians without food (Smith, 54). That same year, the United States’ milling industry had a surplus of grain and plans to aid Russia were drafted by that November (Edgar). This national relief initiative was headed by William C. Edgar (editor of the Northwestern Miller, a Minneapolis trade journal), who contacted the Russian minister in Washington to propose that a shipment of six million pounds of flour be sent to help (Edgar). Edgar then reached out to the millers across Minneapolis (known as “Mill City” by the 1880s) to ask for donations and assemble a team to oversee the flour’s distribution (Smith).

At the time, Reeve (then a Colonel) owned the Holly Flour Mill and was approached by Edgar’s ally, Minnesota Governor William R. Merriam, with the opportunity to become a Relief Commissioner (Edgar). He was joined by Edgar and Edmund J. Phelps, the secretary-treasurer of a Minneapolis loan and trust company (Edgar). After a three-month delay, as Edgar dealt with accusations of exaggeration, fought legal impediments, and struggled to find a willing shipping company, the “mercy” steamship Missouri left port the afternoon of March 16th, 1892 (Smith, 57). Reeve set sail the first week in March and met Edgar and Phelps in St. Petersburg on the 30th (Edgar).

They were received by the U.S. minister to Russia at his home and introduced to the U.S. consul-general and Count André Bobrinsky, a representative of the czar’s special relief commission (Smith, 58) and most likely the “A. Brobrinskaya” named on the canister lid. Two days later, they made their way to Libau (now the Latvian city of Liepaja) and supervised the resulting 241 freight car deliveries to 75 towns and villages in 13 different provinces (Smith, 59). Though there is no written account of this, it is likely the commissioners were presented with famine bread by Bobrinsky during their stay in Libau, and it is then that Reeve would have acquired it. By April 13th, the deliveries were completed, and Reeve and Phelps began the journey home, leaving Edgar to further explore Moscow (Edgar).

Reeve’s canister shows the ingredients of famine bread (known to the Russians as “Lebeda”) to be straw, stable refuse, tree bark, and rye (Stevens, 146). The canister contains 3 pieces of the “bread,” possibly make-shift slices, that look almost like modern oat-granola bars in that the dry materials have been compressed together with some kind of binding agent and baked. This binding agent was likely a small amount of water or, unfortunately, the “stable refuse,” which helps explain why so many Russians fell ill from eating it (Stevens). W. Barnes Stevens, a Daily Chronicle correspondent reporting from Russia during the famine, details the ailments incited by the bread which included: “swellings, dysentery, typhus, and various other complaints” (Stevens, 146). These ailments often lasted two to three weeks and left the affected person “delirious, or so weak as not to be able to rise” (Stevens, 131). The majority of the deaths were caused by this weakness, as their immune systems were not strong enough to fight off opportunistic infection (Spignesi).

Stevens even mentions an account from an orphanage ran by “a Russian lady of high rank” (Countess Bobrinskaya herself!) where the children “preferred to die of hunger sooner than feed on this composition” because eating it caused them “such violent pains in the stomach” (Stevens, 146). When given the chance to try some himself, Stevens described it as “sour, bitter, and unpalatable…largely adulterated with sand” (Stevens, 37).

The southeastern city of Samara was considered to be “one of the governments most affected by the famine” (Stevens, 12). Located at the convergence of the Volga and Samara rivers, Samara exists today as “an important cultural, industrial, economic, political, and social center in European Russia,” and is Russia’s sixth-largest city as of the 2010 census (Migiro). However, in 1892, Samara saw an “influx of the famine-stricken [that increased] rapidly” and lost the majority of its cattle, which made it doubly impossible to effectively plough and re-plant (Stevens, viii). Famous Russian author Leo Tolstoy and his wife, Countess Sophia Andreyevna Tolstaya, owned a farm in Samara and Tolstoy made frequent trips to provide food and fuel to those who needed it (Lilly). Russian farmers made the journey to Samara to receive aid, and often ended up settling there because “there [was] nothing left in [their] villages” as any grain they might have salvaged was commandeered by Russian officials and replaced with inedible famine bread (Stevens, 97). There is one recorded instance in which a hungry peasant was so desperate that he entered a wealthy merchant’s home and “threatened to break all the mirrors unless he was given money to buy bread” (Stevens, 139).

In his position as a member of the czar’s special relief commission, it is likely that Count Bobrinsky made at least one journey either from his home in Bogoroditsk or from his office in St. Petersburg to Samara to assess the state of the peasants and strategize how to best help them. He likely procured some famine bread to demonstrate the peasants’ dire need in the meantime. It is as likely that the bread was acquired in his own hometown, as Bogoroditsk was “a centre of one of the distressed districts…[and] the whole family of the Bobrinskys had been busily engaged…in the work of relief” (Stevens, 26). This possibility raises the question, then, of why Reeve specified the famine bread as being from Samara, so the former becomes the more plausible inference.

In the lead-up to the famine, grain harvests came in at about half of the usual yield and the affected area covered about 17 provinces on either shore of the Volga, the largest and longest river in Europe that primarily runs through Central Russia (Simms, 237). This area was equivalent in size to “double the size of France or equal to the entire American Midwest, from Ohio to North Dakota” (Simms, 237). Leftist Russian thinkers largely placed the blame for the famine’s spread and intensity on the Russian government, citing their continued export of grain taken from the country’s reserves while their own citizens had nothing (Lilly). They called for the export to cease and the grain to be redistributed, as well as for the updating of farm equipment and the education of the rural famers so that they could be introduced to “better agricultural techniques” to prevent future scarcities (Simms, 239).

Leo Tolstoy led the charge by publishing an article called “A Terrible Question” in the Moscow Gazette that “opened the eyes of the government to the crisis” (Lilly). He also set up “eating rooms” that provided two meals for a day’s labor and “soup booths” in 22 of the hardest hit villages (Lilly). This article was published just two weeks before Edgar contacted the Russian minister in 1892, making it likely that Edgar’s “European agents” would have passed it on and it was part of what inspired him to take action (Smith, 56).

Even with the aid from the United States, Russia did not return to normal until the following harvest. Throughout, Tolstoy continued his support and joined the outcry over the Russian government’s mismanagement of the relief effort that, according to the protests, not only prolonged the famine but worsened its overall impact (Lilly).

Further Reading

Edgar, William Cromwell. 1893. The Russian Famine of 1891 and 1892: Some Particulars of the

Relief Sent to the Destitute Peasants by the Millers of America in the Steamship Missouri:

a Brief History of the Movement, a Description of the Relief Commissioners’ Visit to Russia, and a List of Subscribers to the Fund (version digitized by Google). Minneapolis, MN: The Millers and Manufacturers Insurance Co. https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5Qafob887KpnqZ58UI0yI_JZ1w_t0Vq5dik1Wj8nJLgI4eqM-g8eD6fGCSinCikyutE5TNLLLFYib1eSy348VNQrNMtQiStrCZLjUxCERVI0tifIQcJChcujCZSF97Wp8V27R7UCSS1tOUmFFHtZWlSq0n9vux-yUr3i6B2KE_BQvFMarKoaDK_vwq_PFc001JNwk9y-DzIQ7pBCDObkxnUdfuqEJANOKRyybw16iOux4Seh7EidLYFxsPwve-ohYY5Lcaw0GuUQiO04grDQFnhlP8Wi2bAWyHJA6W4HDkxYzfowsqpU

Lilly, David P. 1995. “The Russian Famine of 1891-92.” Loyola University Student Historical Journal 1994-1995 26: 1–9.

http://people.loyno.edu/~history/journal/1994-5/documents/TheRussianFamineof1891-1892.pdf.

Mac, Linda, and Bunny Bo. “Andre Alexandrovitch Bobrinsky (1859-1930).” Find a Grave. Find a Grave, August 4, 2013.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/114909704/andre-alexandrovitch-bobrinsky.

Migiro, Geoffrey. November 2018. “20 Biggest Cities in Russia.” WorldAtlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/20-biggest-cities-in-russia.html.

Reeves, Francis Brewster. 1917. Russia Then and Now: 1892- 1917; My Mission to Russia during the Famine of 1891-92. New York, NY: The Knickerbocker Press. https://archive.org/details/russiathennow18900reev/mode/2up.

Simms, James Y. 1982. “The Crop Failure of 1891: Soil Exhaustion, Technological Backwardness, and Russia’s “Agrarian Crisis”.” Slavic Review 41, no. 2: 236-50.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2496341.

Smith, Charles E. May 1892. “The Famine in Russia.” The North American Review https://www.jstor.org/stable/25102370.

Smith, Harold F. 1970. “Bread for the Russians.” Minnesota History. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/42/v42i02p054-062.pdf

Spignesi, Stephen J. 2002 “The 1891 Russia Famine.” In The 100 Greatest Disasters of All Time, 50–52. New York, NY: Citadel Press.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Catastrophe/OOav5YTAJAC?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

Stevens, W. Barnes. 1893. “The Truth about Russian ‘Famine Bread.’” British Medical Journal vol. 1,1673: 146.

Stevens, William Barnes. 1892. “Through Famine-Stricken Russia.” Google Books. Sampson Low, Marston. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=OUY4AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&pg= GBS.PP1.

Tolstoy, Leo. December 21, 2017. “A Terrible Question.” Translated by Nathan Haskell Dole. Wikisource, the free online library. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Terrible_Question.