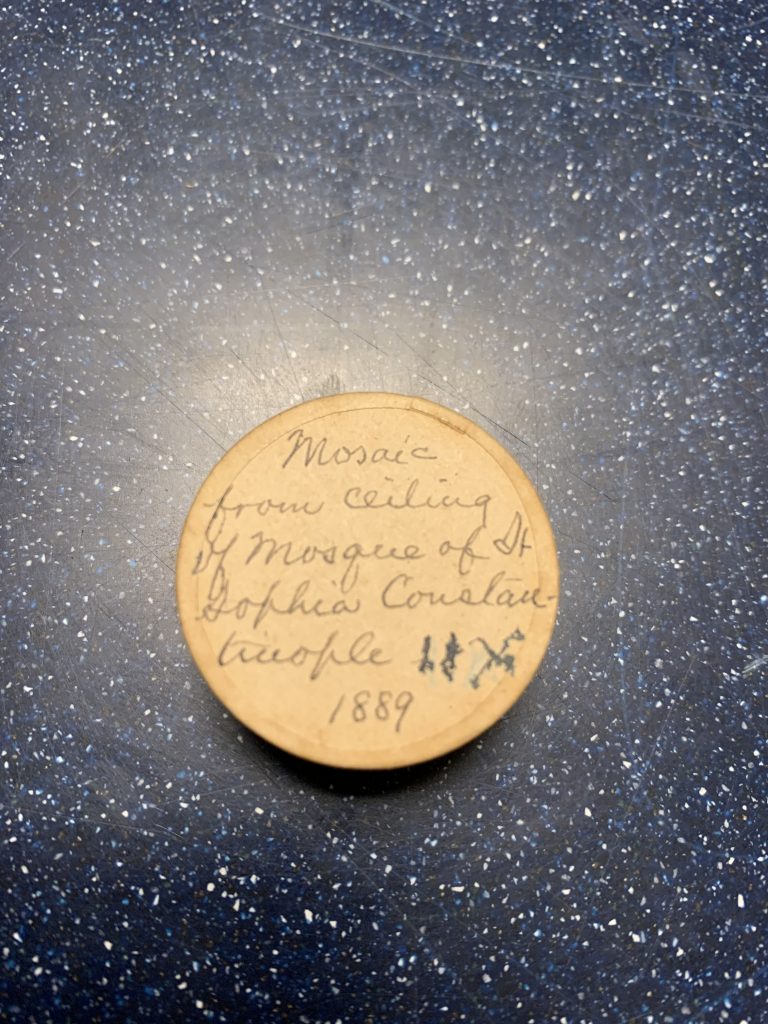

- 1948-64-118, Mosaic from Ceiling of Mosque of St. Sophia Constantinople, 1889

- Istanbul, Constantinople (Now Turkey), 41.0086° N, 28.9802° E

- Date Acquired: 1889

- BM# 1948.64.118

Donated by Charles Reeves, a canister holding a piece of red mosaic from the ceiling of St. Sophia (Hagia Sophia) located in Constantinople (now Istanbul), Turkey. Acquired by Charles Reeve during his stop in Constantinople on his expedition and published in “How We Went and What We Saw”, this piece of red mosaic was acquired from the Church of Hagia Sophia built by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (527-565 AD) and converted to a mosque after A.D. 1453. The piece of red mosaic conveys the memory of Hagia Sophia’s mosaics surviving the period of Iconoclasm (no religious imagery) (726-87 A.D., 815-43 A.D.) and the sack of Constantinople by the Venetians and the Crusaders of the 4th Crusade in 1204. It is a relic of Byzantine art during the glory of the Byzantine empire. Later the mosaics would be covered in plaster when the Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople.

The mosaics of Hagia Sophia are the only examples of Byzantine mosaics in this period. Known mosaics of the elaborate Byzantine mosaics are the reestablishment of the Orthodox church and the reigns of Basil I and Constantine VII. The deesis of the triforium, depicting Christ receiving the supplication of his mother and John the Baptist is the most important item of Byzantine mosaic art. Another is the depiction of Jesus Christ receiving Constantinople from Constantine and Hagia Sophia from Justinian and shows the artistry that could be completed in the 9th-10th century.

Hagia Sophia is located in Istanbul, Turkey formally known as Constantinople. The city was created by Constantine to be a new Rome and was the highlight of the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Justinian (527-565 A.D.) ordered Hagia Sophia’s construction to be completed by Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Turkey after the Nika Riots destroyed the previous church (Madden 2016, 113-16). Justinian wanted to make the building bigger and more lavishly decorated (Madden 2016, 113). This included marbles of all color, mosaics, windows, and gold covered domes but were later torn down during the sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 (Madden 2016, 114).

The construction was a single project that lasted five years and ten months between 532- 537 A.D (Emerson and Van Nice, 1950, 2). Hagia Sophia was built to be the main church used by the Greek Orthodox Empire and was the world’s largest church for almost 1000 years. The original dome of Hagia Sophia collapsed in 558 A.D., six months after an earthquake racked Constantinople. The following renovation project rebuilt Hagia Sophia’s original dome with fixes on the main piers and corrected any deformations. The project completed with the crown 6.25 meters higher than the original. The dome has a single brick shell with a span of 33 m and contains 40 windows separated by 40 ribs (Emerson and Van Nice, 1950). Subsequently Hagia Sophia’s dome will be repaired on the western arch in 986 A.D. and eastern arch in 1347.

Following this was a period of iconoclasm (no religious imagery) in the 8th century following the sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders. The Crusaders then raided Hagia Sophia which led to the building being stripped of its gold and mosaics and led to Hagia Sophia being burned down (Madden 2016, 93). The Emperor’s belief that Constantinople moved away from god and is why the city was sacked led plastering of any religious imagery. Subsequently was a restoration of mosaic decoration, following another sack of the city in 1204 A.D., due to the destruction of Hagia Sophia’s mosaics the history of the earliest mosaics is unknown. Hagia Sophia has withstood burning, pillaging, plagues, and time. It now functions as historical museum that opened in February 1935 (Madden 2016, 216, 93, 194-95).

Hagia Sophia will be converted into a mosque as a of conquest and dominion of Constantinople by Mehmed II after sieging the city in 1453 (Madden 2016, 253). Once Hagia Sophia was converted, any remaining mosaics were covered with plaster due to the prohibition on figural art in Islamic religious imagery (Madden 2016, 256). In 1847 the Fossatti brothers, Swiss architects appointed to restore Hagia Sophia and repair the mosaics are allowed to restore the mosaics where they also created identical records for the mosaics they recovered (Teteriatnikov 2013, 61). In 1889, Charles Reeve was able witness the restored mosaics before they were destroyed in the earthquake of 1894, where the mosaics the Fossatti brothers recorded would disappear (Teteriatnikov 2015, 273, Reeves 1891, 347).

Until 1931, the mosaics remained covered until a restoration and recovery program started under the leadership of Thomas Whittemore (Madden 2016, 346). In 1934, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Turkey’s first president and leader of the Republican People’s Party (Zurcher 2017, 183), the head of Istanbul’s westernization and secular movement ordered Hagia Sophia to become a museum while recovery and restoration of the building would be expanded (Madden 2016, 347). It was no longer a mosque but a “unique architectural monument of art”. Any remaining mosaics that formerly covered the interior of Hagia Sophia with impressiveness are now sparse.

Visited by Reeve in his trip to Constantinople in 1889, Reeve remarks that Hagia Sophia is the largest of the Mosques, but Solyman (Sullimani Mosque) is the most beautiful (How We Went and What We Saw 1891, 347). The Süleymaniye Mosque was created after Hagia Sophia based on inspiration from it to create a better version of it, while Hagia Sophia itself served as the sultan’s mosque for centuries (Madden 2016, 346). Hagia Sophia is located in Istanbul, Turkey formally known as Constantinople. The city was created by Constantine to be a new Rome and was the highlight of the Byzantine Empire.

Now the present painted decoration is rough, out of scale, and distracting. The remnants of the mosaics that formerly covered everything with impressiveness are sparse. The really fine marble revetments and shafts are dull and shabby (Charles, 1930, 326).

For Further Reading:

- Morey, C. 1944. “The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 2, no. 7 (1944): 201-10. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3257129.

- Charles, M A. 1930. “Hagia Sophia and the Great Imperial Mosques.” The Art Bulletin 12, no. 4, 321-45. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3050788.

- Emerson, W., and Van Nice, R. L. 1950. “Hagia Sophia: A Unique Architectural Achievement of the Sixth Century.” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 4, no. 2. 2-3. www.jstor.org/stable/3822741.

- Teteriatnikov, N. B. 2013. “The Mosaics of the Eastern Arch of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople: Program and Liturgy.” Gesta 52, no. 1, 61-84. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669685.

- Whittemore, T. 1942. “The Unveiling of the Byzantine Mosaics in Haghia Sophia in Istanbul.” American Journal of Archaeology 46, no. 2, 169-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/499381

- Casson, S. 1934. “The Mosaics of St. Sophia.” The American Magazine of Art 27, no. 12, 634-40. www.jstor.org/stable/23933254.

- Teteriatnikov, N. 2015. “The Last Palaiologan Mosaic Program of Hagia: The Dome and Pendentives.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 69, 273-96. www.jstor.org/stable/26497719.

- Ousterhout, R. 2004 “The East, the West, and the Appropriation of the Past in Early Ottoman Architecture.” Gesta 43, no. 2, 165-76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25067103

- Hayden, R. M. 2016. “Intersecting Religioscapes in Post-Ottoman Spaces: Trajectories of Change, Competition, and Sharing of Religious Spaces.” In Post-Ottoman Coexistence: Sharing Space in the Shadow of Conflict, New York; Oxford: Berghahn Books, 59 https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1kgqw2h.7

- Lebon, J.H.G. 1971. “The Islamic City in the Near East.” Ekistics 31, no. 182, 64-71. www.jstor.org/stable/43619961.

- Oikonomides, N. 1976. “Leo VI and the Narthex Mosaic of Saint Sophia.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 30, 151-72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291393.

- ÇAĞAPTAY, SUNA. 2011. “Frontierscape: Reconsidering Bithynian Structures and Their Builders on The Byzantine-Ottoman Cusp.” Muqarnas 28 ,157-93. www.jstor.org/stable/23350287.

- Komins, B. J. 2002. “Cosmopolitanism Depopulated: The Cultures of Integration, Concealment, and Evacuation in Istanbul.” Comparative Literature Studies 39, no. 4, 360-85. www.jstor.org/stable/40247365.

- Tanyeri-Erdemir, T., Hayden, R. M., and Erdemir, A. 2014. “The Iconostasis in The Republican Mosque: Transformed Religious Sites as Artifacts of Intersecting Religioscapes”. International Journal of Middle East Studies 46, no. 3, 489-512. www.jstor.org/stable/43303182.

- Fleming, K. E. 2003. “Constantinople: From Christianity to Islam.” The Classical World 97, no. 1, 69-78. https://www.jstor.org /stable/4352826

- Taylor, R. 1996. “A Literary and Structural Analysis of the First Dome on Justinian’s Hagia Sophia, Constantinople.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 1, 66-78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/991056

- Deringil, S. 1991. “Legitimacy Structures in the Ottoman State: The Reign of Abdulhamid II (1876-1909).” International Journal of Middle East Studies 23, no. 3, 345-59. www.jstor.org/stable/164486.

- Bogdanović, J. 2016 “The Relational Spiritual Geopolitics of Constantinople, the Capital of the Byzantine Empire.” In Political Landscapes of Capital Cities, 97-154. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1dfnt2b.9.

- Ousterhout, R. 1996. “An Apologia for Byzantine Architecture.” Gesta 35, no. 1, 21-33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/767224.

- Krautheimer, R. 1986. “The Hagia Sofia and Allied Buildings,” Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, 201-237. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rodley, Lyn. 2010. Byzantine art and architecture: an introduction. Milton Keynes, UK: Lightning Source UK Ltd

- Reeve, C. M. 1891. “How We Went and What We Saw” 347. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons

- Madden, T. F. 2016. “Istanbul: City of Majesty at the Crossfords of the World,” 77, 216, 105, 113-116, 270-71, 345-47, 194-98, 206, 251, 254, 255-56. New York: Viking.

- Zurcher, E. J. 2019. “Turkey a Modern History”. I.B. Tauris. 183