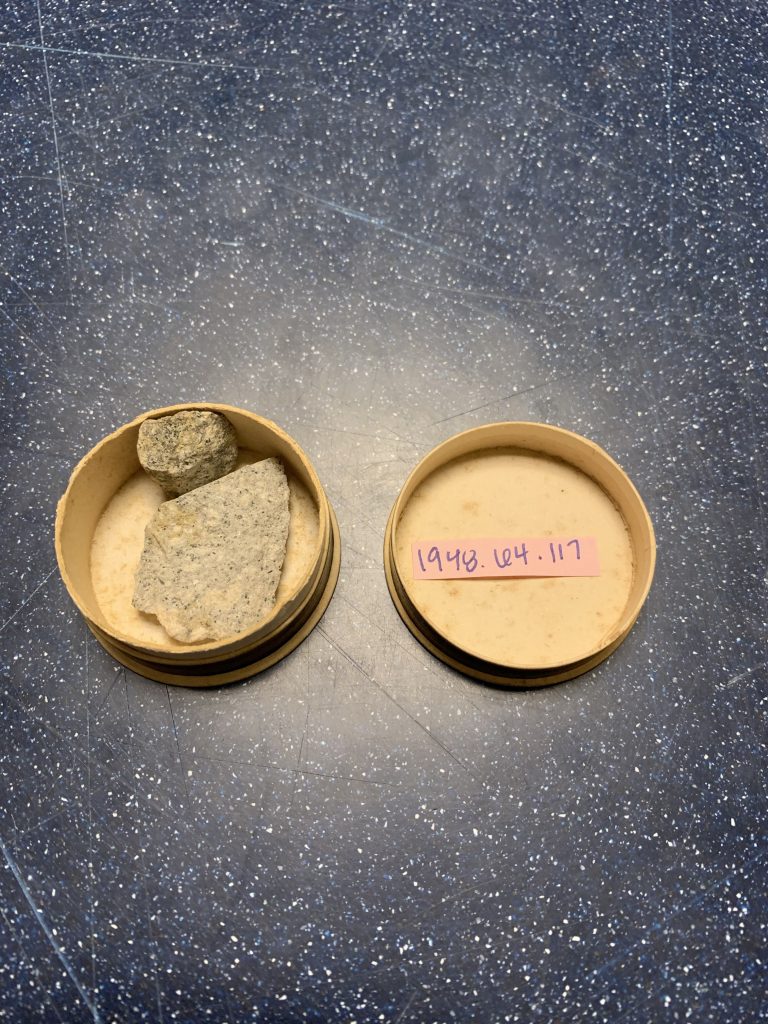

Stone from one of the Interior Columns of the Cologne Cathedral

Canister with Reeve’s Handwritten Label

- Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, 50.9413° N, 6.9583° E

- Date Acquired: 1892

- BM# 1948.64.117

A canister holds two chips of speckled stone from an interior column of the Cologne Cathedral. It was acquired by Charles Reeves when Cologne Cathedral was undergoing repairs. Reeves visited Cologne, Germany in 1892 on an expedition to the Russian relief mission. The stones, fragments of interior columns of the Cologne Cathedral likely date to 1248 when Cologne Cathedral’s construction began on the Feast of the Assumption of Mary.

Cologne Cathedral is a Catholic cathedral in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany and the pride of its people. It holds the seat of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the administration of the Archdiocese of Cologne (UNESCO, 2020). In 1996 it was declared a World Heritage site. It is Germany’s most visited landmark and receives about 20,000 people a day. Cologne Cathedral was declared a World Heritage Site in 1996 by UNESCO as monument of German Catholicism and Gothic architecture. When creating the plans to build the cathedral to be the tallest twin-spired church in the world reaching 515 ft (175 M), the engineering technique had to be better than the Romanesque style before it (Owen 1989, 96).

Gothic architecture design and construction allowed for verticality and was favored for its ability to hold structure (Ziolkowski 2018, 240). Which allowed the attractive design of Gothic high towers and arches that also functioned on geometrical support (Simson 1952, 8). Gothic architecture’s use of a pointed arch meant that there could not be heavy pillars or columns in the interior of the church. This also meant that the walls had to be thin with the support of buttresses (reinforcements), a new method that allowed for the architect to create buildings that would not be restricted (Owen 1989, 96). The two pieces of speckled stone that is a mixture of grey, beige, and black are remnants from such a column that would support the unrestricted arches in the interior of Cologne Cathedral.

Cologne Cathedral’s narrow central aisle or nave leads to the choir. At 144 meters, it is longest nave in Germany and flanked by two aisles along each side (Cologne Tourism 2020). Aspects of Cologne includes its abandonment of the engaged column derived from Chartres to implement a clustered arcade pier, which is a group of shafts that rise straight up without interruption to the springers of the vaults, that has gleaming glazed triforiums that are similar in work of a filigree due to the elimination of small arches from the pendentives (Cologne Cathedral, Cork 2020). Outside the outward and downward thrust of the vault is absorbed and channeled by flying buttresses in the French manner.

The reason for the construction was due to the want of having a building good enough to house the remains of the Three Wise Men, which Archbishop Rainald von Dassel brought to Cologne from Milan when the city was conquered in 1164. Due to these relics, the Cologne Cathedral has become one of the most important locations of pilgrimage in Europe (UNESCO 2020).

The construction of the Cologne Cathedral would help create jobs for the laborers of the city and create growth in the economy of Cologne (Owen 1989, 95). The cornerstone of Cologne’s Gothic cathedral was built on the Feast of the Assumption of Mary on 15 August 1248 and replaced previous structures (Cologne Tourism 2020). In 1842, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV laid the foundation stone marking the continuation of construction to complete the cathedral (cologne.de, 2020). The construction project drew builders like Friedrich Schmidt, who spent 15 years at the restoration of Cologne Cathedral between 1845-1860 while Vincenz Statz worked as the leading church architect from 1841-1861 (Sisa 2002, 1).

In the Early 16th Century, building construction was stopped due to lack of money and interest. During the 19th century the German Romantic movement created interest to complete construction and drew national attention. Though over six centuries and finishing in 1880, Cologne Cathedral marks the pinnacle of cathedral architecture (UNESCO 2020). Cologne Cathedral’s powerful message represents the strength and persistence of the Christian religion in medieval and modern Europe.

“Rich am I myself, and willing to make myself poor for such an end. Rich is my capital, rich is Cologne, which shall not be niggardly in a work, which is to make it the first city of Christendom. And in all lands, as far as the cross is held in reverence, shall the call go forth, and the faithful contribute to this godly work.” -Archbishop Conrad of Hochsteden. 1247 (The Crayon, 1855, 351).

Housing the relics of the Three Wise Men, brought by Archbishop Rainald von Dassel from Milan when the city was conquered in 1164, the Cologne Cathedral has become one of the most important locations of pilgrimage in Europe (UNESCO 2020). The Cathedral also houses the Gero Crucifix that was made during the 10th century from the Chapel of the Holy Cross (Burg 1947, 346). Also, in the Cathedral is the Shrine of the Magi built between 1189-1225 and is one of the largest reliquary shrines in Europe (UNESCO, 2020). The earliest documented Corpus Christi procession recorded in Cologne, is somewhere between 1264 and 1279, starting at the parish church of St. Gereon (Holladay 1989, 478). The Cathedral additionally hosts almost untouched paintings above the choir stalls that are dated soon after 1322, the year the cathedral was consecrated (Borenius 1932, 220).

The Cathedral would inspire artists like Huygens and Van der Vinne in many of their paintings because they considered Cologne and Cologne Cathedral to be the new Rome (Bikker 2006, 280). This was also the opinion of many priests and residents in the city. “: “Cologne… is staunchly Roman Catholic, and there is barely a religious order of the Roman church that is not here in the city”- Van Der Vinne”.

But in Chartres and Reims during this period of reconstruction and culmination, there was tension with the populace of the city and the interests of the cathedral clergy. The cathedral frequently opposed the will of the townspeople who viewed the Gothic architecture as unfavorable in buildings other than Cologne Cathedral, while the clergy wanted to continue construction Gothic architecture (Bork 2003, 27).

For Further Reading:

- “The Cologne Cathedral.” 1855. The Crayon 2, no. 23, 351-53. www.jstor.org/stable/25527307.

- Burg, M. 1947. “Romanesque Art at Cologne.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 89, no. 537, 346. www.jstor.org/stable/869596.

- Borenius, T. 1932. “The Gothic Wall Paintings of the Rhineland.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 61, no. 356, 219-24. www.jstor.org/stable/865113.

- Spurr, D. 2012. “Allegories of the Gothic in the Long Nineteenth Century.” In Architecture and Modern Literature, 99-141. ANN ARBOR: University of Michigan Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1qv5nb5.8

- Holladay, J. A. 1989. “The Iconography of the High Altar in Cologne Cathedral.” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 52, no. 4, 472-98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1482466

- Sisa, J. 2002. “Neo-Gothic Architecture and Restoration of Historic Buildings in Central Europe: Friedrich Schmidt and His School.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 61, no., 170-87. https://www.jstor.org /stable/991838

- Bikker, J. 2006. “Cologne, the “German Rome,” in Views by Berckheyde and Van Der Heyden and the Journals of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Tourists.” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 32, no. 4 273-90. www.jstor.org/stable/20355338.

- Von S., Otto G. 1952. “The Gothic Cathedral: Design and Meaning.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 11, no. 3, 6-16. https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.rollins.edu/stable/987608

- Fingesten, P. 1961. “Topographical and Anatomical Aspects of the Gothic Cathedral.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 20, no. 1, 3-23. https://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.rollins.edu/stable/427347

- Ziolkowski, J. M. 2018 “Point Taken: Gothic Modernism and the Modern Middle Ages.” In The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity: Volume 3: The American Middle Ages, 239-300. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv5zfv24.9.

- Bork, R. 2003. “Into Thin Air: France, Germany, and the Invention of the Openwork Spire.” The Art Bulletin 85, no. 1, 25-53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3177326

- The Cologne Cathedral. Cologne.de “ https://www.cologne.de/what-to-do/the-cologne-cathedral.html”

- Cologne Cathedral. Unesco. “World Heritage List: Cologne Cathedral” https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/292/

- Owen, V. L. 1989. “The Economic Legacy of Gothic Cathedral Building: France and England Compared.” Journal of Cultural Economics 13, no. 1, 89-100. www.jstor.org/stable/41810419.

- Nussbaum, Norbert, and Scott Kleager. 2000. “The Development of Gothic Architecture in Germany.” German Gothic church architecture, 49-85. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Frankl, Paul, and Paul Crossley. 2001. “The High Gothic Style.” Gothic architecture, 105-186. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

- Cologne Cathedral. Cologne Tourism. “Cologne Cathedral” https://www.cologne-tourism.com/see-experience/poi/cologne-cathedral/